Are Teachers Driving The Public/Private Sector Earnings Gap?

A great deal of the debate surrounding public sector unions focus on how much public employees earn versus private workers. Every credible analysis – those that account for huge differences between public and private workers in terms of characteristics like profession, education, and experience – find that public compensation is competitive or lower than that of private-sector workers (for recent examples, see here, here, and here, or a review here).

I have, however, heard a few thoughtful observers make the point that virtually all these analyses include education workers, and that this might be a little misleading. It’s a fair point. Roughly one in five state/local government employees are in fact K-12 teachers, while another five percent are professors at public colleges and universities. This is important because analyses of public/private sector compensation essentially compare public employees with workers with similar characteristics (education being the most important one) in the private sector. The research above indicates that workers with more education pay a larger “price” for working in the public sector, whereas many lesser credentialed, lower-skilled government jobs actually pay more. Since many teachers have master’s degrees (and professors Ph.D.’s), and they are such a huge group, it’s reasonable to wonder if they might be skewing the overall estimates.

So, I decided to see if a comparison of public/private compensation that does not include teachers and professors would yield very different results. Let’s take a look.

In a previous post, I used U.S. Census data (American Community Survey, available from IPUMS.org) to break down the public/private gap in wage and salary earnings, controlling for state, work schedules, experience, and education. Here, I replicate this analysis, but exclude K-12 teachers and college/university professors (both public and private).

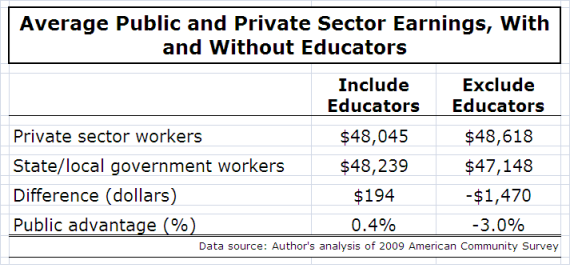

Let’s first see how average public/private earnings compare before and after educators are excluded (note: none of these analyses includes benefits).

The exclusion clearly makes a difference. It increases the average private sector salary (probably because private school teachers are poorly paid), while decreasing the public sector average over $1,000.

But this comparison, of course, does not account for differences among workers in terms of key wage-determining factors such as education and experience. When those differences are controlled for, it is almost certain that the earnings gap found in my previous post (about 20 percent) will be lower, since the public sector workers included in the analysis will be less educated, on average, than they were when teachers were included.

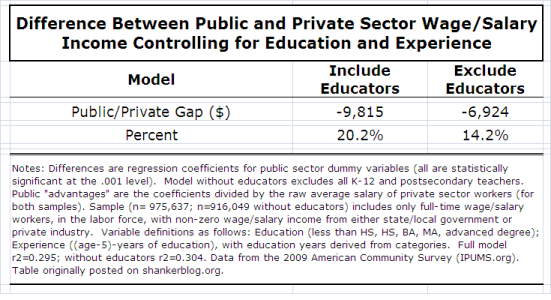

In the table below, I present the results from the previous post, along with the public/private gap when educators are left out. The models control for work schedules (hours and weeks), state, gender, experience, and education. The details are in the table stub, if you’re interested.

The results show that excluding teachers and professors does mitigate the public/private earnings gap – reducing the "advantage" for private sector workers from 20.2 percent to 14.2 percent – but the difference remains large.

This illustrates the fact that more educated, highly-skilled workers - such as teachers and professors - suffer a more substantial earnings penalty for government work. When a large group of the most educated workers is excluded – i.e., educators – the gap is narrower. But it is still huge – around 14 cents on the dollar.

So, it is certainly true that educators are “responsible” for part of the public/private earnings gap. They are the dominant public employee group, and would therefore exert considerable influence on the results, no matter what.

Nevertheless, with or without teachers and professors, public employees’ wage and salary earnings are substantially lower than those of comparable private sector workers.

This illustrates the fact that more educated, highly-skilled workers – such as teachers and professors - suffer a more substantial earnings penalty for government work

Two significant flaws, though:

1) You're just looking at wages, right? This doesn't account for the very expensive benefits that some teachers get; as we've seen in Milwaukee, benefits are worth an additional 74% on top of wages. Not that all teachers get this level of benefits, but it's a potentially huge source of bias here.

2) This analysis seems to treat all educational levels as equivalent. But that's clearly wrong: a master's in education is not the same as a master's in computer science or engineering, and there's no reason to expect the economic reward to be equivalent.

Stuart,

Regarding your first point, you’re correct that the analysis is of earnings (income from wages and salary) and not benefits, as I pointed out repeatedly throughout the post.

I would have gladly included benefits, but detailed data are not collected by most major surveys, including the Census. But we can get a rough idea from the BLS (Q4 2010), even though I can only crudely adjust these figures for differences in education, etc. (by comparing teachers with other professionals). The average ratio of *total* benefits to salary costs for U.S. public sector teachers is 0.415, and 0.469 for all public sector (state/local) professionals. For private sector professionals, the ratio is 0.417.

If you want to include only health and retirement benefits (as Robert Costrell did in the WSJ article you are referencing), the BLS does not permit one to separate out teachers for these more detailed estimates of benefits, but the average ratio (September 2010) for all public sector professionals is 0.339, compared with 0.225 among private sector professionals (and 0.241 for all private sector workers). So, if the 74 cents figure for Milwaukee is accurate, it would appear to be a giant anomaly. (Source: http://bls.gov/ncs/ect/)

I would also add that benefits-to-salary ratios present a rather incomplete picture when it comes to assessing whether a group of workers is “overcompensated” (which is the focus of this post). For example, low-wage workers who also get health insurance would have very high ratios, even though their total compensation is modest (just as high-earners would have lower ratios, even though they might be well-compensated). As you know, higher (health/retirement) benefits-to-salary ratios among public employees probably indicate that they trade salary for these benefits. This "tendency" has other potential implications (e.g., budgeting uncertainty for state/local governments), but total compensation among public employees is competitive with or lower than that among comparable private sector workers.

As for your second point, although you’re probably correct that the returns to an education master’s are a bit less than those to an engineering degree, the entire purpose of the analysis in this post is to look at the public/private gaps when teachers are *excluded* from the sample.

Thanks for the comment,

MD

although you’re probably correct that the returns to an education master’s are a bit less than those to an engineering degree

The returns ought to be only a small fraction, given the relative difficulty and meaningfulness of each respective master's degree. Which is why I think this conclusion is massively unproven:

more educated, highly-skilled workers – such as teachers and professors - suffer a more substantial earnings penalty for government work.

How so? To conclude this, you'd need (at a bare minimum) to compare public school teachers with master's degrees in education to non-public school teachers with master's degrees in education. A comparison of teachers with master's degrees in education to private sector workers with master's degrees in other fields doesn't tell us anything.

"How so? To conclude this, you’d need (at a bare minimum) to compare public school teachers with master’s degrees in education to non-public school teachers with master’s degrees in education. A comparison of teachers with master’s degrees in education to private sector workers with master’s degrees in other fields doesn’t tell us anything."

How does it tell us nothing? It shows that teachers, with their attained level of education, could earn more if they chose to enter the workforce, and therefore there isn't that monetary incentive to go into teaching for many people-- many people recognize that even if they like the idea of teaching, their wages will be higher in another job in the private sector.

See this article, for example, (I don't know if it's any good) which looks at teacher wages over time and compared to the private sector.

http://www.nea.org/home/14052.htm

"It shows that teachers, with their attained level of education, could earn more if they chose to enter the workforce"

No, it doesn't. To put it bluntly, the market wages earned in the private sector by people with masters' degrees in business or computer science or engineering tell us absolutely nothing about what public school teachers with masters' in education would supposedly earn if they left public schools and tried to find work elsewhere. Outside of private schools, a masters' in education isn't going to be worth much to any private sector employer, is it?

But private school wages are much lower on average than public school wages: NCES reports that "In 2007–08, the average annual base salary of regular full-time public school teachers ($49,600) was higher than the average annual base salary of regular full-time private school teachers ($36,300).”

Where in the private sector would masters' degrees in education be worth anything at all, let alone more than in public schools?