The Narrative Of School Failure And Why We Must Pay Attention To Segregation In Educational Policy

Our guest authors today are Kara S. Finnigan, Associate Professor at the Warner School of Education of the University of Rochester, and Jennifer Jellison Holme, Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Finnigan and Holme have published several articles and briefs on the issue of school integration including articles in press in Teachers College Record and Educational Law and Policy Review as well as a research brief for the National Coalition on School Diversity. This is the first of a two-part blog series on this topic.

Imagine that you wake up one morning with a dull pain in your tooth. You take ibuprofen, apply an ice pack, and try to continue as if things are normal. But as the pain continues to grow over the next few days, you realize that deep down there is a problem – and you are reminded of this every so often when you bite down and feel a shooting pain. Eventually, you can’t take it any longer and get an x-ray at the dentist’s office, only to find out that what was originally a small problem has spread throughout the whole tooth and you need a root canal. Now you wish you hadn’t waited so long.

Why are we talking about a root canal in a blog post about education? As we thought about how to convey the way we see the situation with low-performing schools, this analogy seemed to capture our point. Most of us can relate to what happens when we overlook a problem with our teeth, and yet we don’t pay attention to what can happen when we overlook the underlying problems that affect educational systems.

In this blog post, we argue that school segregation by race and poverty is one of the underlying causes of school failure, and that it has been largely overlooked in federal and state educational policy in recent decades.

Our research has focused on the ways that students are segregated from one another across school district lines by race and by social class, and educational policies that seek to reverse these trends (see Finnigan & Holme, 2015; Finnigan et al, 2015; Finnigan, Holme, & Sanchez, in press; Holme & Finnigan, 2013; Holme, Finnigan, & Diem, in press).

The nation’s failure to address school segregation has created a serious, deep-seated problem, analogous our decaying tooth story: policymakers have sought to address symptoms (i.e. failing schools, high dropout rates) with various solutions (accountability, market-based reforms) and yet, while some of these steps make the problem somewhat or temporarily better, the underlying maladies persist and, in fact, often serve to undermine those very reform efforts.

As we note in a forthcoming article in Education Law and Policy Review (written with Joanna Sanchez), when ESEA was passed in 1965, two competing policy solutions to educational inequality were proposed. One, embodied by the ESEA legislation, was to deliver more funding and targeted supports to low-income students. The other, promoted by civil rights advocates, was to integrate schools. This latter approach was premised both upon the principle of social justice and, as James Ryan (2010) argues, on the assumption that school quality for all students would be improved by “tying” the fate of whites and non-whites together.

Beginning in the late 1970s, however, political and legal support for school desegregation began to diminish, while support for school-based interventions increased. As a result, renewals of ESEA became increasingly focused on “reforming” whole urban schools via comprehensive school reform, and later in the 1990s and 2000s, through standards and accountability. Our research suggests, however, that these efforts have largely treated symptoms (low achievement, dropouts, etc.) rather than some of the deeper underlying causes (concentrated poverty and racial segregation). Let’s look at a few maps from our studies to demonstrate this point.*

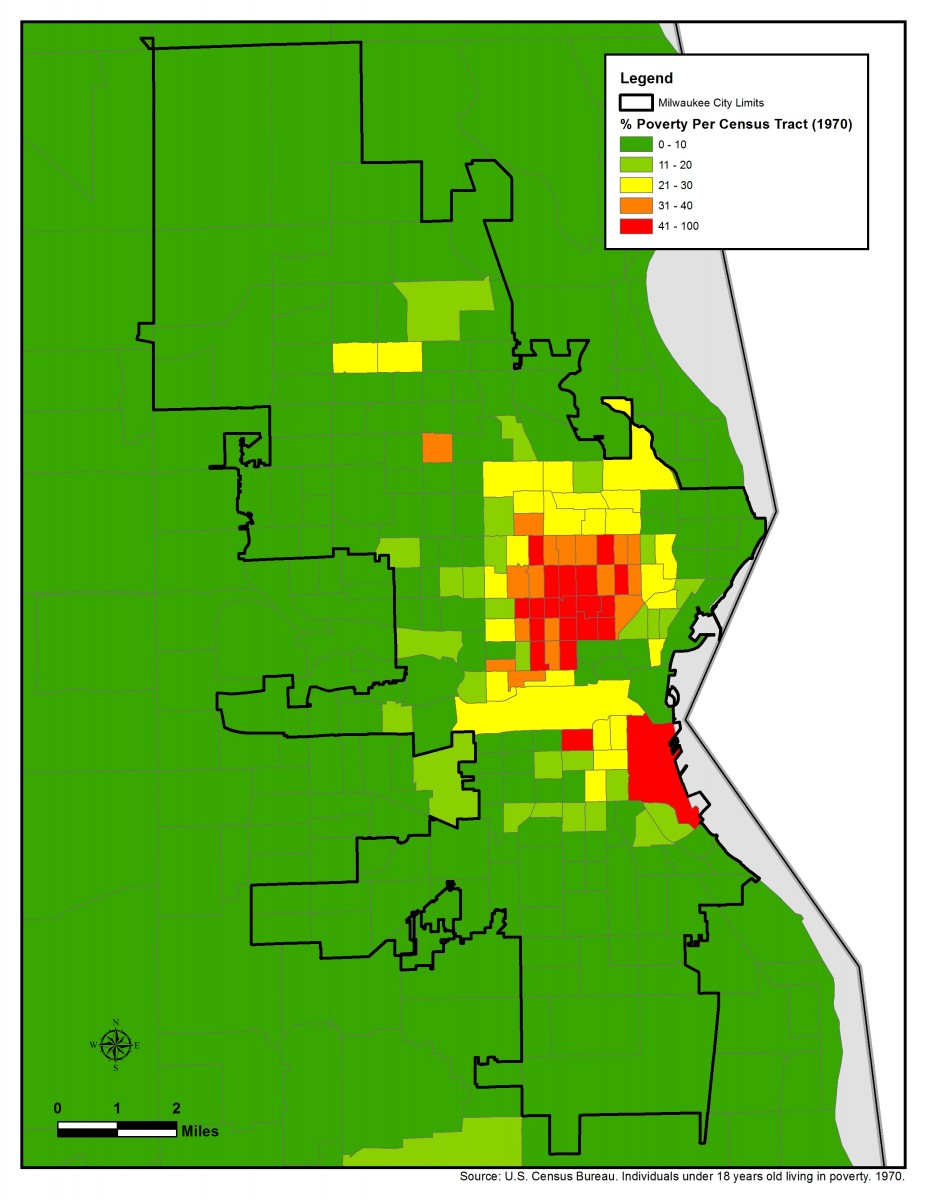

Map 1: Percent Poverty in Milwaukee Per Census Tract 1970

Map 1 shows the geography of poverty in 1970 in Milwaukee, one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country. This segregation was the result of intentional federal, state, and local policy, which kept the growing population of African Americans out of the suburbs via restrictive covenants and realtor discrimination. At the same time, bank and insurance company redlining fueled disinvestment in the urban core neighborhoods to which African Americans had been confined (as seen in Map 2). In fact, the high level of racial and socioeconomic segregation in schools resulted in a lawsuit which was filed around the time of the passage of ESEA, followed by a judicial ruling in 1976 to desegregate the school district – a sort of early diagnosis of the problem that has been largely ignored ever since.

Over time, the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) grew even poorer and more segregated. These poverty rates were compounded by economic restructuring that affected cities throughout the industrial Midwest. By the early 1980s, the city/suburban racial divide grew so stark that the MPS filed a suit against the suburbs and the State alleging that these patterns could only be fixed through a metropolitan desegregation plan. The resulting settlement in 1987 was a very modest plan, so modest in fact that it left basic school district boundaries unchanged.

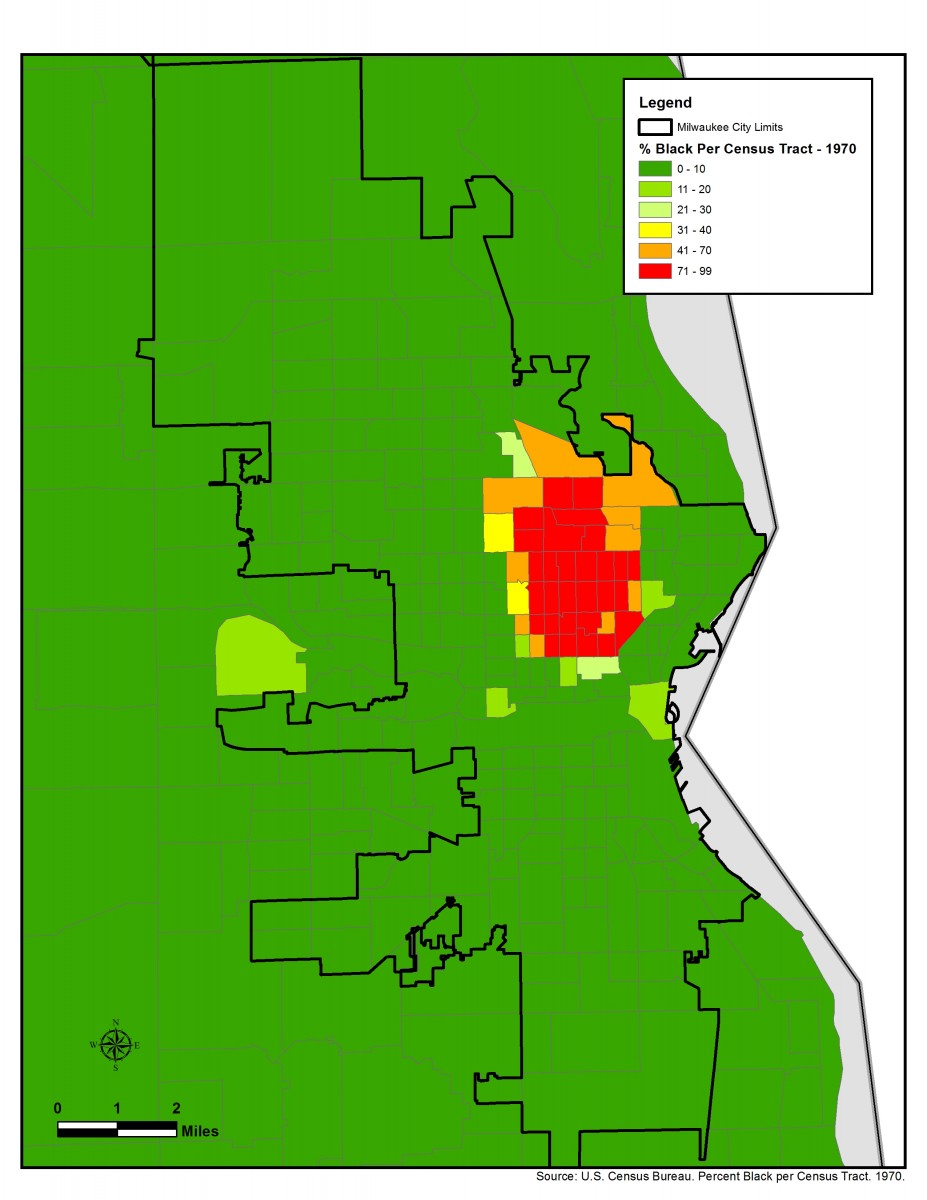

Map 2: Percent by Race in Milwaukee Per Census Tract 1970

As our maps illustrate, over the course of four decades, segregation and the concentration of poverty in Milwaukee grew even more severe. The changing demographics from 1970 to 2012 include growing populations of Hispanic families who primarily reside in neighborhoods just south of the city center, with African American families residing north of the city center. In the 2012 maps, we combine the percentages of African American and Hispanic families to show the contrast with the predominantly white areas within and outside of Milwaukee district lines.

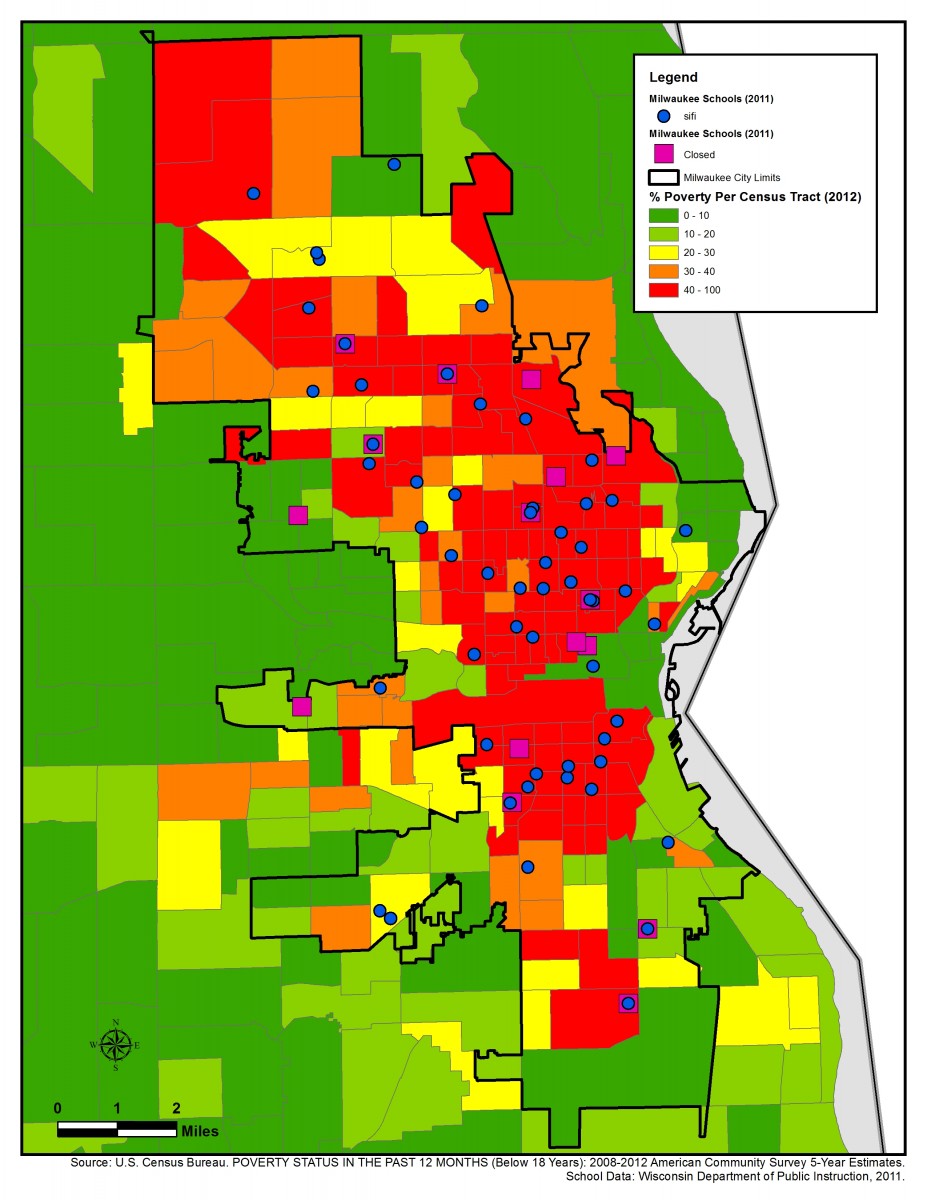

Map 3: Schools Identified For Improvement (SIFI) and Poverty

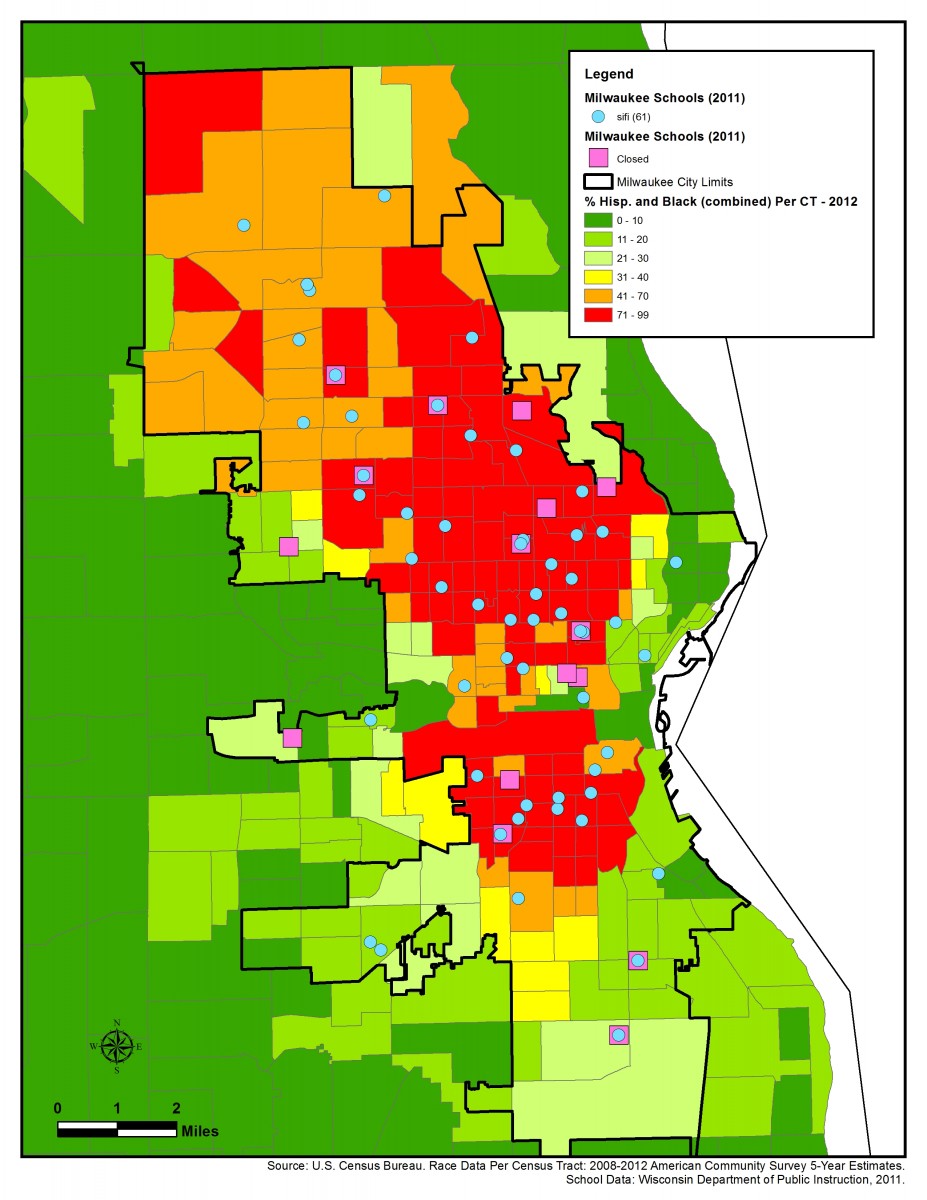

These segregation patterns are important to educational policy because they correspond closely with perceived patterns of school “failure.” Policymakers attempted to address these school failures through a variety of approaches: school-based interventions, standards and accountability, and charters and vouchers. And, while these solutions may have served to address some aspects of the problem, our maps illustrate that they have not been able to dramatically improve achievement for students across the system. In Map 3 and Map 4, we show with a blue dot where each of the SIFI schools are located in the greater Milwaukee area (including in the suburbs, though none exist there).**

Indeed, 83% of all failing schools in the state of Wisconsin are located in Milwaukee and nearly all of the SIFI schools are located in census tracts that are 41-100% poverty and 41-100% Black and Hispanic.

Map 4: Schools Identified For Improvement (SIFI) and Race

These maps suggest the need for policy to consider that segregation is among the root causes of school failure. Research has linked segregation and concentrated poverty in schools to a variety of negative educational outcomes: depressed student achievement, reduced resources, high rates of teacher and leadership turnover, and increased dropout rates, among others.

In Milwaukee, schools continue to struggle among the growing isolation, continued white and middle class flight, and related challenges that come along with the concentration of poverty including health, safety, and economic challenges in these communities. These problems are not confined to Milwaukee; high levels of school segregation are present in many urban and increasingly suburban school districts. It is time for federal and state policy to tackle one of the primary, underlying causes of school failure, rather than just the symptoms, by dealing with patterns of racial and economic segregation. In our next blog post, we will flesh out how the recently passed Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) could be leveraged to address these issues.

*****

* Special thanks to Joanna Sanchez, a Ph.D. student in Educational Policy at the University of Texas at Austin, who produced the maps for our study.

** Until 2012, the state labeled schools that failed to meet standards under the accountability system as “Schools Identified for Improvement” (SIFI). We were able to correspond this data with Census data through 2012. After 2012, the state received a NCLB waiver and began using different labels yet the patterns have not changed very much since the time of our maps.

1) Are there examples of

1) Are there examples of cities where desegregation and economic development during the same period co-occurred with improvement in the schools?

2) Do you have data/analyses of the impact of white flight in the period you describe on measurable improvement ( or failure) in inner cities that at one time were integrated?