Amazon Workers: The Struggle For Human Rights And Workplace Dignity

Our guest authors today are Norman and Velma Hill, lifelong activists in the Civil Rights and Labor movements. Norman Hill served as the president of the A. Philip Randolph Institute from 1980 to 2004, the longest tenure in the organization’s history. He remains its president emeritus. His wife of 60 years, Velma Murphy Hill, was an assistant to the president of the United Federation of Teachers, during which time she led a successful effort to organize 10,000 paraprofessionals working in New York public schools. She was subsequently International Affairs and Civil Rights Director of the Service Employees International Union.

One of the most gratifying aspects of living a long life is realizing that the best history refuses to stay put as history. Nearly 60 years ago, we stood among the quarter of a million people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial as civil rights activists and organizers of the monumental 1963 March on Washington.

What many may need to be reminded of today is that this demonstration of soaring speeches, righteous demands, and the power of broad-based and racially diverse coalitions, were as much about the second decade of the 21st century as they were about the midpoint of the 20th.

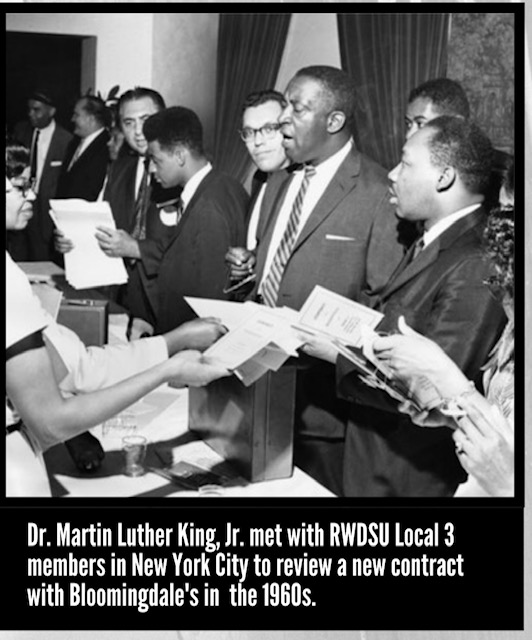

The movement’s leadership, characterized in iconic figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., Walter Ruether of the United Automobile Workers union, and A. Philip Randolph, himself a storied labor leader, could not then specifically see a behemoth employer called Amazon, or a valiant struggle of thousands of its warehouse workers in north-central Alabama. But men and women like King, Ruether and Randolph could see, with crystal clarity, the inextricable binding of economic insecurity with the most persistent, virulent forms of racial discrimination and disparities of justice and opportunity. They understood, as we do, that free and independent labor unions are essential to this nation’s democratic society.

It was no accident that the full title of the March on Washington included the words for Jobs and Freedom. We all knew that there could be no full guarantee of civil rights without good jobs and workers’ rights, and that meant, by and large, organized labor and trade unionism.

Similarly, it must be noted that the struggle being waged in Bessemer, Alabama by 5,800 Amazon workers is mostly being fought by Black women. It is a battle marbled with obvious racial dimensions, much like the striking Black sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee who drew King into that city’s multilayered race and labor dispute in 1968, and, months later, to his assassination there.

Recall the “I AM A MAN” signs Black sanitation workers carried in protest. They plainly spoke to not only their struggle to secure a decent wage and safe working conditions on the job, but also to their right to human dignity in the workplace.

The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which has been organizing workers at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, has been unequivocable about the interactionalism of race and labor in its attempts to establish a union at the massive warehouse.

We believe that the Amazon workers facing down their employers stand on the shoulders of the likes of Rosa Parks of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott of the mid-1950s, and of young people, supported by the Black community, who in 1963 faced down stinging firehoses and snarling police dogs in Birmingham, Alabama while protesting racial segregation.

“We see this campaign as much as a civil rights struggle as a labor struggle,” Stuart Appelbaum, the union’s president, recently told The New York Times.

In overcoming Amazon’s fierce, corporate resistance to unions in its facilities—starting with Bessemer—supporters of this campaign for a union could well stir a resurgence in union organizing, first in the South, and then into more union-sympathetic areas in the North and West. Moreover, labor’s success in Alabama could inspire a cascade of similar efforts that could well gain workers higher wages and better working conditions, but also usher in for them some measure of control in the workplace.

We must never forget that workers in Alabama are issuing a clarion call to low-wage workers in Amazon facilities around the country and the 1.1 million Amazon workers worldwide to stand up for their human rights.

Amazon has loudly and often stated that it already pays its workers a starting wage of at least $15.30 an hour and offers full-time workers and some of its part-time employees medical benefits. But what Amazon does not offer, proponents of unionizing there say—and we agree—is a voice in their workers’ own affairs. Without union protections, what an employer gives, an employer can take away.

A vote for the union is a vote for job security, safety and stability.

The vote and what it represents has garnered the attention of Democratic strategist and organizer Stacey Abrams, numerous professional athletes, actors like Danny Glover and Tina Fey, political figures like Senator Bernie Sanders, and even President Joseph Biden, who recently issued one of the strongest pro-union statements for any president in decades.

In this classic clash of corporate and worker interests lays a promise of profoundly important implications that at once speak to race in America, while also transcending race. This duality of purpose and outcome should not come as a surprise. Every small step and leap forward that marked civil rights advances of decades past always signaled change and benefits to the nation as a whole, to helping to make a more perfect America for all its people of every hue, gender and background.

King often emphasized this point, and we hear a similar call today underscored by anti-poverty leaders like the Rev. William Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign.

In Alabama, Black workers are in the vanguard of a struggle of self-determination in the workplace, a workforce in this case that is 85 percent African American, yet mindful that what happens in Bessemer—win or lose—will likely quake across the nation.

Randolph realized the stakes to our democracy at the intersection of civil rights and labor rights more than 60 years ago. “Equality is the heart and essence of democracy, freedom, and justice, equality of opportunity in industry, in labor unions, schools and college, government, politics, and before the law,” he said. “There must be no dual standards of justice, no dual rights, privileges, duties, or responsibilities of citizenship. No dual forms of freedom.”