Efforts to help strengthen and improve public education are central to the Albert Shanker Institute’s mission. This work is pursued by promoting discussions, supporting publications and sponsoring research on new and workable approaches to ensuring that all public schools are good schools. As explained by Al Shanker below, these efforts are grounded in the belief that a vibrant public school system is crucial to the health and survival of the nation:

"...I believe that public education is the glue that has held this country together. Critics now say that the common school never really existed, that it’s time to abandon this ideal in favor of schools that are designed to appeal to groups based on ethnicity, race, religion, class, or common interests of various kinds. But schools like these would foster divisions in our society; they would be like setting a time bomb.

"A Martian who happened to be visiting Earth soon after the United States was founded would not have given this country much chance of surviving. He would have predicted that this new nation, whose inhabitants were of different races, who spoke different languages, and who followed different religions, wouldn’t remain one nation for long. They would end up fighting and killing each other. Then, what was left of each group would set up its own country, just as has happened many other times and in many other places. But that didn’t happen. Instead, we became a wealthy and powerful nation—the freest the world has ever known. Millions of people from around the world have risked their lives to come here, and they continue to do so today.

"Public schools played a big role in holding our nation together. They brought together children of different races, languages, religions and cultures and gave them a common language and a sense of common purpose. We have not outgrown our need for this; far from it. Today, Americans come from more different countries and speak more different languages than ever before. Whenever the problems connected with school reform seem especially tough, I think about this. I think about what public education gave me—a kid who couldn’t even speak English when I entered first grade. I think about what it has given me and can give to countless numbers of other kids like me. And I know that keeping public education together is worth whatever effort it takes."

Albert Shanker, 1997

-

-

Citizen Power Challenge Grant Winners

Classroom projects such as learning about global cultural perspectives as a way to build compassion, planning a community garden to promote healthy eating, combating bullying, learning American Sign Language and building a health and wellness library are some of the 15 winning projects in the Citizen Power Challenge. The challenge, funded by the Aspen Institute’s Pluribus Project, is sponsored by the American Federation of Teachers, the Albert Shanker Institute and First Book. More information and list of winners.

-

2016-2017 Conversations

List of the 2016-2017 Conversations. Please note that due to the election, the first Conversation will be held the third Wednesday in November. There will be no December Conversation. The Conversations will resume in January, February, March, April and May. -

Reclaiming the Promise of Public Education Conversation Series

Sponsored by the Albert Shanker Insitute and the American Federation of Teachers, this monthly conversation series is designed to engender lively and informative discussions on important educational issues. We invite speakers with diverse perspectives, including views other than those of the Albert Shanker Institute and the American Federation of Teachers. What is important is that these participants are committed to genuine engagement with each other. Watch the past conversations and register for upcoming conversations. -

The Allocation of New Students to New York City High Schools

A research project documenting the characteristics and assignment of students who enter New York City's high school choice process for the first time.

-

Let’s Talk: Professional Development Modules

The highest rate of vocabulary development (and corresponding acquisition of background knowledge) occurs during the preschool years. This makes preschool a crucial time for effective, content-rich instruction. Accordingly, the Institute has developed a series of Common Core State Standards (CCSS)-aligned modules, which are designed to strengthen the ability of early childhood educators to impart rich, academic content in fun, developmentally appropriate ways. The modules cover the academic domains of oral language development, early literacy, early science, and early mathematics.

-

CTE 2014: Career Training for the Knowledge Economy

This conference, sponsored by the New York Citywide CTE Advisory Council, the United Federation of Teachers, and the NYC Department of Education, with support from the CTE Technical Assistance Center of New York State, the American Federation of Teachers, the Albert Shanker Institute, and the Association for Career and Technical Education. was a special addition to the annual professional development day for New York City CTE teachers.

-

The Social Side of Education Reform

The Social Side is a lens that brings insight into a critical oversight in educational reform and its policies: Teaching and learning are not solo accomplishments but social endeavors -- they are best achieved, through trusting relationships and teamwork, instead of competition and individual prowess.

-

A Novel Approach To Understanding Teachers' Work & Work Context

The University of Wisconsin and the Albert Shanker Institute are jointly developing the Educator Day Reconstruction Method, which provides a new and flexible way of measuring teachers' work and the broader context where it unfolds. The Educator DRM can be adapted to meet a district's information needs and can be used to complement existing data sources. We view this customization process as something to be accomplished collaboratively, with districts and stakeholders.

-

The Good Schools Seminars

This seminar series is part of an effort to build a network of union leaders, district superintendents, and researchers to work collaboratively on improving public education through a focus on teaching. It emerges from the Albert Shanker Institute’s role as sponsor of provocative discussions about education and public policy reform.

AFT/SML/ASI Book Club A Conversation with Kamala Harris

AFT/SML/ASI Book Club with Dashka Slater

AFT President Randi Weingarten held a timely conversation with journalist Dashka Slater about her book, Accountable. Through the lens of a real incident at a California high school involving a racist social media account, Slater examines how students, educators and a community grappled with harm, responsibility, and the consequences of actions taken in online spaces.

High Quality After School Programming: What Does it Look Like and How to Get It

This webinar demystifies what high-quality after-school time programming looks like, empowers caregivers to advocate for access, and promotes accountability across after-school programs.

A Conversation with Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider

Join us for our September AFT Book Club session featuring AFT President Randi Weingarten and distinguished authors Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider, discussing their compelling new book The Education Wars: A Citizen's Guide and Defense Manual

A Conversation with Charles Blow and Randi Weingarten

Join us for our May AFT Book Club session featuring AFT President Randi Weingarten and renowned author Charles M. Blow, discussing Blow's memoir Fire Shut Up In My Bones. Engage with Weingarten and Blow as they explore the multifaceted themes reflecting on the complexities of identity, trauma and resilience within the backdrop of a segregated Louisiana town. Blow's ability to weave his personal narrative with broader social critiques makes the memoir a compelling read for anyone interested in the intersections of personal experience and public advocacy.

AFT Book Club: Conversation with Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Randi Weingarten

This groundbreaking new book club series is brought to you by the AFT, Share My Lesson and the Albert Shanker Institute. Tune in each month for an evening of inspiration, intellect and innovation—where the power of words takes center stage! Each month you will hear a fusion of words and wisdom as influential authors, scholars and activists engage in a riveting dialogue that promises to ignite your passion for literature and social change.

PASSION MEETS PURPOSE: Promising Pathways Through Experiential Learning

The Albert Shanker Institute, the AFT, and the Center for American Progress held a pioneering conference on experiential learning: PASSION MEETS PURPOSE: Promising Pathways Through Experiential Learning. The conference showcased the dynamic realm of experiential, hands-on learning, where students engage in immersive educational experiences that foster curiosity, exploration, inquiry, and profound comprehension. This conference highlighted various facets of experiential learning, ranging from career and technical education (CTE) to the arts, music, and action civics. Through student-centered approaches, participants delved into how experiential learning cultivates deeper understanding and equips students with the skills necessary for promising careers across diverse fields.Reading Reform Across America Webinar

Join this webinar on Sept. 19 at 6:30 PM ET with Share My Lesson and the Albert Shanker Institute to learn how to implement the latest reading reform goals to deepen literacy support.The Intersection of Democracy and Public Education

The Shanker Institute and Education International are both celebrating milestone anniversaries in 2023. Both organizations share a common origin, Albert Shanker cofounded EI and was the inspiration for the ASI. To recognize the common origin and priorities of each organization, strengthening public education and committed to democracy, this Panel Discussion & Anniversary Celebration of the Albert Shanker Institute (25 Years) and Education International (30 Years) was held ahead of the International Summit on the Teaching Profession to take advantage of both organizations’ leaders being in Washington, DC at the same time.

Teaching About Tribal Sovereignty

This session is part of the series: A More United America: Teaching Democratic Principles and Protected Freedoms.

Available for 1.5-hour of PD credit. A certificate of completion will be available for download at the end of your session that you can submit for your school's or district's approval. Watch on Demand.

-

From the Simple View of Reading to an Integrated View of Foundational Skills

Our guest author is Rafely Palacios, a first-grade bilingual teacher and literacy advocate in the Bay Area, recognized by the ILA 30 Under 30 for her work improving literacy outcomes for multilingual learners.

If you’re a teacher, you’ve likely encountered the Simple View of Reading (SVR). This model shows that reading comprehension results from two essential components: decoding (word recognition) and language comprehension (understanding spoken language). In many U.S. classrooms, these components are taught in separate instructional blocks: phonics for decoding and, later, a distinct time for comprehension or oral language.

But could this separation have unintended effects on students’ development as readers?

In Elbow Room, a paper recently published by the Albert Shanker Institute, Dr. Maryanne Wolf challenges a siloed interpretation of the Simple View of Reading, shown by the separation of decoding and comprehension blocks in many classrooms. Instead, Dr. Wolf argues for a more integrated approach to foundational skills. Rather than treating decoding and language comprehension as parallel but separate strands, she emphasizes that children must develop word recognition, word meaning, syntax, and morphology as interrelated components within a coherent instructional sequence. Dr. Wolf argues that each skill, and their integration, must be taught explicitly, systematically, and cumulatively, ensuring no component is left to chance, while remaining dynamic enough to adapt pace and support to each learner's needs.

I recommend this paper to all primary-grade teachers. Dr. Wolf’s work broadens our understanding of how we act as architects for our students, revealing how every lesson and interaction reshapes a child’s mind. It answers questions we often have about why some students struggle, showing that the 'magic' happens when our instruction helps them integrate skills rather than teach them in isolation. In this post, I share key ideas from Dr. Wolf’s paper and reflect on how they are shaping my own first-grade reading instruction.

-

When “Success” Leaves Students Behind: How Market-Based Schools Exclude Students with Disabilities

As a freshly licensed teacher, I entered the profession hoping to challenge common stereotypes about teaching. I was ready to defy persistent myths of the ‘jaded teacher’ who re-used their lesson plans year after year and taught from their desk chair. So, I sought an environment where teachers taught with rigor and acted as advocates for change. When I encountered a job listing for a national charter school network, it felt like the perfect place to teach: the network emphasized high expectations for both staff and students, all in the name of helping disadvantaged communities beat the system.

Once the school year started, every moment of lesson prep and execution was centered around a single goal: excellence. As the year progressed, the administration increasingly painted certain students as threats to this goal students who struggled to comply with the demanding curriculum and constant test taking. These students—many of whom were multilingual learners and had a learning disability—were many grade levels behind. The strict behavioral regime didn’t accommodate their needs, and they were often in the dean's office instead of participating in instructional time. But when I questioned what we could do to support them, I encountered pushback. They will learn to meet the expectations. We need to focus on the cuspers. Because we were compared to other charters in the district, my leadership wanted to prioritize “cuspers”—students on the verge of advancing performance categories, whose gains would most directly improve accountability metrics—over students who were severely under proficient and therefore viewed as unlikely to advance brackets.

That school year taught me a lot about the nuanced and tense views on how to help disadvantaged students succeed in a world of standardized success. However, a broader question stuck with me years after this experience: To what extent do charter and private schools exclude students with disabilities within a highly standardization education system? Existing research confirms that charter and private schools do, in fact, exclude students with disabilities—- not only by discouraging initial enrollment, but also by pushing students out after enrollment.

Due to the rapid expansion of charter schools and the widespread adoption of private school voucher programs in many states, this research is all relatively new. However, one argument that has consistently championed the charter movement is that charter schools perform slightly better than traditional public schools on standardized tests. This stance became less clear as research has muddied reported score growth when accounting for student demographic and location. More recently, political verbiage has shifted to center priorities like educational freedom and parent choice to push for market-based schools. Beyond political rhetoric, this shift raises important questions about the larger costs to public education. Here are three key patterns that demonstrate how market-based schools exclude students with disabilities.

-

What Changed My Mind About How to Teach Reading

This guest essay features Claude Goldenberg, Professor Emeritus of Education at Stanford University, who shares how his thinking about teaching reading changed through close work with colleagues who held very different views, and how that experience points to a broader lesson about how teachers learn, how assumptions shift, and how practice can improve. It is adapted from a recent podcast episode of Literacy Across Languages. Learn more in his Substack 'We Must End the Reading Wars... Now."

When I went to college, I thought I'd go to law school or something like that. Education was not in my sights. But I found out in college there was a program you could take to get a teaching credential. My roommate told me, you know, before we go to law school, it might be good to get a teaching credential. It won't mess up your schedule. You don't have to take bulletin boards 101 or anything, and it will give you something to do for a year or two before going to law school. I said, okay, that sounds okay. As it turned out, over the remaining years I got more interested in education and less in law.By the time I graduated from college, my parents were living in San Antonio. And I thought, well, I could go back there and teach because in addition to being interested in education, I spoke Spanish. So I thought that was sort of an additional skill I could bring to the proceedings.

I considered different places, but I always wanted to work with kids who just, you know, don't have the opportunities that I grew up with, and how many of the people in my socio-demographics grew up.

I wanted to teach history, my major in college, but I was offered a job as an eighth grade reading teacher in probably the poorest school district in Texas. Back then I thought, well, the more impossible the assignment, the more I wanted it. The students I’d teach were kids who, in eighth grade, were reading so poorly that the principal said, you can’t have your elective—you’re going to take remedial reading. And he assigned me, a first-year teacher, wet behind the ears and with very little preparation. And I struggled. I mean, it was hard. I had a lot of “ganas,” you know, a lot of wanting to help. But I realized I just didn’t know that much. I really didn’t have very good teacher preparation. Not to disparage anyone or any program, but I just wasn’t prepared. And so I decided to go back to graduate school and try to learn something—to understand why these kids were arriving in seventh and eighth grade so far behind academically.

-

PTECH is #1

Our guest author is Stanley Litow, author, Breaking Barriers: How P-TECH Schools Create a Pathway From High School to College to Career and The Challenge for Business and Society: From Risk to Reward; columnist at Barron's; trustee at the State University of New York (SUNY); professor at Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs; and Shanker Institute board member.

Affordability is issue number one for Americans. They want the price of groceries, gas, childcare and health care to be more affordable and want government leaders to stop being distracted and make this their number one priority. But there is a component of the affordability crisis that goes beyond the cost of goods and services and has received little attention. It's making sure more Americans have the funds to afford a middle-class lifestyle as a means of addressing affordability. This means attention on the education and workplace skills needed to ensure not just a job, but career success Better quality education is one key to solving the affordability crisis. This means our schools and colleges embracing reforms that ensure far more youth have the education and skills to achieve career and economic success. This can be done, but it requires leadership at all levels.

This brings us to some good news. Fifteen years ago, an innovative high school opened in Brooklyn, New York. The school, called PTECH, had a core goal, to create a seamless pathway from school to college to career. Instead of a grade 9-12 high school with no connection to college or career, PTECH would integrate all three. Starting in grade 9 all courses would connect high school with college credit-bearing courses via a scope and sequence so students would take and pass both college and high school courses concurrently, getting both a high school diploma and an AAS degree in 4-6 years. In addition to collaboration and partnership between higher education and K-12 there would be an industry partner providing mentors, paid internships, and priority for employment. The initial school partners were the New York City Public Schools, The City University of New York, and IBM.

-

When Policy Meets Practice: Why School Mandates Often Miss the Mark

The View from the Ground Floor

It’s safe to assume that policymakers have the best intentions when proposing new provisions for schools. Initiatives for literacy, new pedagogical strategies, and requirements for professional development all sound beneficial to the school community. But what do these regulations look like from the ground floor as a teacher?In my experience, many teachers were not fond of change at all. And I didn’t blame them. Teachers who had been at the school for 15+ years had observed nearly every type of change: from the creation of the Common core to the beginning of PLCs and even more recently bans on curriculum regarding DEI, they have seen it all. When these regulations trickle down from the state, administrators typically come up with a plan to disseminate the requirements to their staff. Teachers see the decisions being made and are told to comply with them.

I experienced this discomfort while teaching at a public middle school that needed to comply with a recent bill prioritizing literacy and critical thinking in all classrooms. In response, the administration decided that all staff must post the same vocabulary words on a word wall in their classroom, along with delivering weekly reading comprehension lessons to their homeroom students. This measure was intended to provoke students’ curiosity and level the playing field for students who didn’t know much academic language. But even the best educational ideas, when shared with teachers hastily, impede the positive impact.

On the day before school started, printers were whirring with lists of 20 words like “concur” and “refute,” teachers were concerned about where the word wall would fit in their room, and questions were unanswered on who would be responsible for creating these reading comprehension lesson plans. You might imagine that non-ELA teachers were not happy with this new responsibility—and you would be right. In fact, many teachers skipped through their reading lessons and instead gave students silent reading time. The teachers didn’t understand why this responsibility had been given to them or what effect it would have on students’ well-being, so they didn’t give it their full effort. It was never explained to them.

So, while state legislators have good intentions in their policies, that doesn’t ensure that the legislation will be attuned to teachers' needs or interests, or that it will include the details needed for meaningful implementation. This may lead to a desensitization of new policies for teachers, as they watch mandates come and go without any input in what’s prioritized and why.

-

What Would Bayard Rustin Do? Part 1

Our guest author is Eric Chenoweth, director of the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe and principal author of Democracy Web, an online comparative study guide for teachers, students and civic activists. He worked with Bayard Rustin in various capacities in the late 1970s and 1980s. Eric visited the new exhibition at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, “The Life of Bayard Rustin: Speaking Truth to Power,” which shines a light on Rustin’s central work in the Civil Rights Movement and his contributions to the international peace and human rights movements. It runs through February 2026, and will form the basis of a permanent exhibition in the museum’s expansion planned for 2026. Part 1 of “What Bayard Rustin Would Do” describes the exhibition and the context to Rustin’s work up to 1965. Part 2 describes Rustin’s work and writings in the last 25 years of his life as he faced the increasing backlash to the gains of the Civil Rights Movement. The full article is posted on the Albert Shanker Institute’s March on Washington Resources page.

We live in a reactionary age. Worldwide, the advance of freedom in the previous century did not just stall. It went into reverse. What is shocking many is that this reactionary age has taken root in the modern world’s oldest, richest and most militarily powerful democracy. Donald Trump’s return to the presidency in January 2025 has put him in a position to assert largely unchecked power to reverse America’s progress towards a multiracial democracy.

This period in America would not have surprised the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin. He spent decades working to end a previous period of white reactionary rule in the United States. Yet, soon after the masterwork of his career — the organizing of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom — he began warning of a political backlash against the gains made to end Jim Crow rule and to make the country a full democracy ensuring the right to vote to all citizens. As he that backlash began to manifest, he argued for political strategies and policies to move the country in a radical direction towards greater equality. Whatever situation he found himself, Rustin worked to achieve a more equal, tolerant and pluralist society and a freer world through nonviolent and democratic means. His life and teachings offer guidance on how to respond to today’s global reactionary challenge. A new museum exhibition offers a launching point.

-

Reading Legislation in California and Massachusetts – Is There a Third Path?

Two pieces of reading legislation - one recently enacted in California and another one under consideration in Massachusetts - mark early efforts in these states to align classroom instruction with the broad scientific consensus on how children learn to read, why some students struggle, and which components are essential for effective reading instruction.

There is evidence that reading policies can contribute to improved student outcomes, as seen, for example, in Mississippi. A recent national analysis likewise suggests that comprehensive early literacy laws are linked to gains in elementary reading achievement. While there is no single policy formula – as Matt Barnum notes, states adopting Mississippi-like policies may see meaningful gains but perhaps should not expect Mississippi-sized improvements – it is reasonable to conclude that strong legislation can contribute to raising literacy levels. Yet, these laws' potential, rest heavily on their effective implementation and sustained commitment over time. In this sense, the laws are best understood as setting the stage for reading reform, rather than as guarantees that change will unfold exactly as written.

How can more states move (or continue to move) toward stronger reading laws that set a better stage for improvement efforts? How can legislation meaningfully address something as complex as reading development and the instruction it requires? And what distinguishes laws that are best positioned to succeed? While lessons can be learned from states at the forefront, different contexts will call for different approaches. In this piece, we compare the paths taken by California and Massachusetts and highlight a third, promising model from Illinois, which enacted literacy legislation in 2023.

-

The Mindsets We Bring to Understanding Reading Laws

Earlier this summer, we published a piece clarifying common misunderstandings about reading legislation. We sought to distinguish what truly is—and is not—in the laws we've been tracking and cataloguing for the past three years. Our primary concern is that oversimplifications and selective portrayals of the legislation often divert attention from constructive push back that could genuinely improve reading policy. Still, mischaracterizations persist – not solely because of incomplete or inaccurate readings of the laws themselves, but also due to the deep-seated beliefs and assumptions we all bring into these discussions. Put simply, our pre-existing views inevitably shape our sense making of what’s in these laws.

Supporters of reading legislation generally concur that: (a) U.S. students performance on reading tests is concerningly low; (b) instruction, though not the sole determinant, remains a significant factor in shaping student reading outcomes; (c) many instructional practices and materials currently in use are poorly aligned with the established research consensus on how children learn to read; and (d) aligning these practices and materials more closely with the strongest available evidence would increase reading success for more students.

In contrast, critics often contend that: (a) the purported reading crisis is overstated; (b) external factors such as poverty, the chronic underfunding of schools, or increasing chronic absenteeism to name a few factors, largely shape reading outcomes; (c) many educators already use evidence-based methods and materials; and (d) increased alignment of instruction and materials to the established research base is not guaranteed to meaningfully improve outcomes.

-

Revisiting the Great Divergence in State Education Spending

A few years ago, we took a quick look at the difference in K-12 education spending between the higher- and lower-spending states, and whether that “spread” has changed since the early 1990s. We found, in short, a substantial increase in that variation, one which really started in the long wake of the 2007-09 recession.

Let’s update that simple descriptive analysis with a few additional years of data, and discuss why it’s potentially troubling.

In the graph below, each teal circle is an individual state, and each “column” of circles represents the spread of states in a given year; the red diamond is the unweighted national average. On the vertical axis, we have predicted per-pupil current spending in a district with a 10 percent Census child poverty rate (roughly the average rate), controlling for labor costs, population density, and enrollment. This measure comes from our SFID state dataset (note that the plot excludes Alaska and Vermont).

-

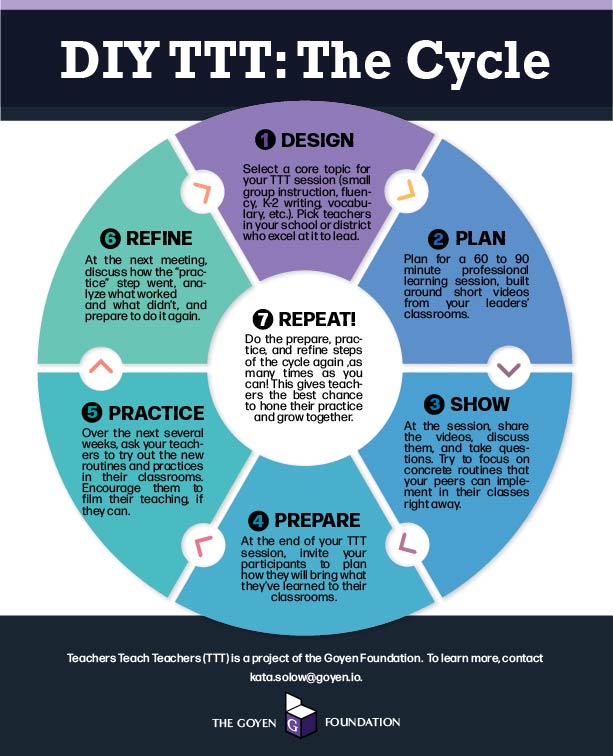

When Teachers Teach Teachers, Teachers Learn

Our guest author is Kata Solow, executive director of the Goyen Foundation, where she led its multi-year transformation process and created the Goyen Literacy Fellowship to recognize exceptional reading teachers.

Elementary school teachers across the country are asking for help.

Go on Facebook, browse Twitter, and you’ll hear a common refrain: “We want to change how we teach reading, but we don’t know where to begin. We need to see what it looks like. Give us models and examples of excellent literacy instruction.”

Why is this happening? For these teachers, their world has just changed. Over the last five years, as reading-related legislation has swept the country, hundreds of thousands of elementary school teachers are being required to change the way they teach reading. This is a really big deal: changing how you teach reading is a hard thing to do.

States are trying to help teachers make these changes. Most of the newly-passed laws support professional development for in-service teachers. However, the most common PD programs like LETRS are highly theoretical. While they provide educators with a strong foundation in the components of structured literacy and the research that underlies it, they do not address what these components look like in a real classroom.

At the Goyen Foundation, we think that we have started to build a model that bridges this research-to-practice gap by providing teachers with concrete examples of great literacy instruction. This piece is about how you can do it in your school or district.

-

How Relationships Matter In Educational Improvement

This short presentation explains some shortcomings of mainstream education reform and offers an alternative framework to advance educational progress.

-

The Emergence of the "Precariat": What Does the Loss of Stable, Well-Compensated Employment Mean for Education?

The emergence of the global knowledge economy has revolutionized the nature of work in America – for the worse. Unionized, well-paying private sector jobs that were once a ladder to the middle class have been decimated. -

The Early Language Gap is About More Than Words

The vocabulary gap between rich and poor children develops very early and it is about more than just words. In fact, words are the tip of the iceberg. So what lies underneath? Find out by watching this three-minute video.

-

The Next Generation of Differentiated Compensation: What Next?

This panel will examine the terrain of teacher compensation from a number of different perspectives, offering their recommendations on what a good compensation

-

How Do We Get Experienced, Accomplished Teachers into High-Need Schools?

If a master designer had created American education as we know it, he would have to be a Robin Hood in reverse, taking from the poor and giving to the rich. American students with all of the advantages of wealth are disproportionately taught by the best prepared, most experienced and most accomplished teachers, while students living in poverty with the greatest educational needs are disproportionately taught by novice teachers who were poorly prepared and who receive inadequate support. -

A New Social Compact for American Education: Fixing Our Broken Accountability System

Twelve years after the passage of No Child Left Behind and five years into Race to the Top, America finds itself in a ‘test and punish’ system of school accountability that poorly serves the nation and its students.

-

Disrupting the Pipeline

The United States accounts for 5 percent of the world’s population, but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners; it is no exaggeration to call our national approach to criminal justice “mass incarceration.” And our prison cells are disproportionately filled with poor men of color, especially African-American men. Mass incarceration is one of the paramount civil rights and economic justice issues of our day.

-

Early Childhood Education: The Word Gap & The Common Core

Given states’ difficulties in implementing the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) thoughtfully, many early childhood educators have begun to worry about what the NAEYC refers to as “a downward pressure of increased academic focus and more narrowed instructional approaches.” But, as the NAEYC’s statement on the CCSS also observed, that “threat also provides an opportunity” for early education to exert more positive, “upward pressure” on the K–12 system. -

Quality Assessments for Educational Excellence

The conversation focused on federal and state policy on student assessment, with an eye to identifying policies that would promote best assessment practices. -

Civic Purposes of Public Education and the Common Core

One of the primary purposes of public education is to foster an engaged and well-educated citizenry: For a democracy to function, the "people" who rule must be prepared to take on the duties and the rights of citizens.