A Legislator’s Lessons From Fifth Graders

Our guest author is Massachusetts State Senator Becca Rausch.

Earlier this year, I walked into one of the elementary schools in my district to visit with the fifth grade –- all 300 of them. (For those who might not work with young people routinely, that is a lot of fifth graders.) School visits and engaging with students is one of my favorite parts of serving in the Massachusetts Senate. Presently, I am the only mother of elementary school aged children or younger in our chamber, and I’ve worked with children for as long as I can remember, so the fact that I love and dedicate real time and energy to youth outreach is unsurprising. But this particular visit sticks with me because of the enormity of its embedded power.

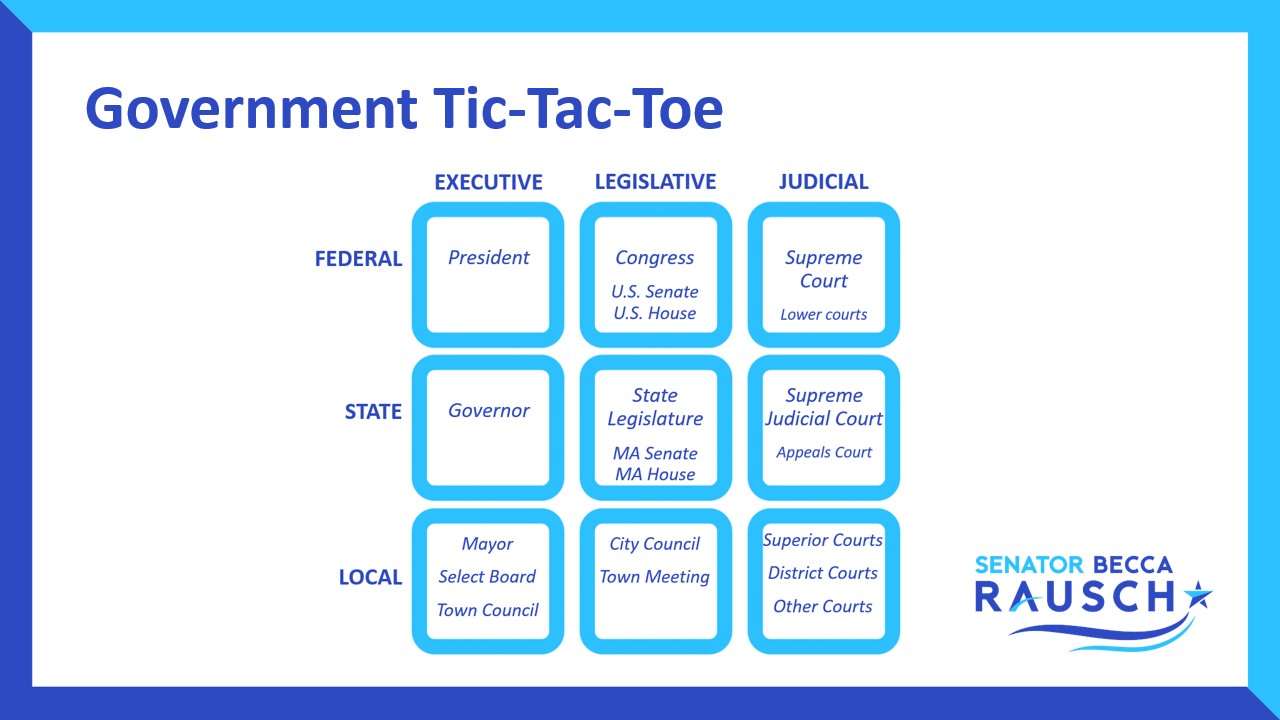

When I speak with students, I always aim to enhance the existing civics education curriculum. I talk about my path to the State Senate through prior elected service in local government. I present students with an interactive “government tic-tac-toe” grid that shows the three branches of government as implemented within the three levels of government systems. Usually, students know most of the federal branches. Fewer know the state branches. Very few know the local government structures.

The fifth graders in that cafeteria knew every single bit and piece. They knew not only the current and former Presidents but also the current and former Governors of Massachusetts, by name. They knew I serve in the State Legislature, along with the names of our two chambers and how many people serve in each. They knew their local government includes a Select Board and Town Meeting. Those students knew civics, regardless of their varying demographics across racial, ethnic, wealth, and other axes. I remain in awe of those amazing kids and their fantastic teachers, and hold such appreciation for all their parents and caregivers who both support their classroom learning and provided the experiential learning that happens every time an adult takes a child to the voting booth.

Systemic shifts simply cannot occur without a solid understanding of the structures of those systems. I went to law school to learn how to use the law as a tool to generate positive social change, but those lessons and resulting access to levers of power should not be reserved for or restricted to those who have the privilege to pursue a legal education, nor should they wait so long. Civics education empowers young people from all backgrounds to make their voices heard as they push for progress on the issues and values that matter most to them. It delivers the experience of influencing law and policy even before students are old enough to vote, so when the time comes for them to start casting their ballots, they know the immense importance of exercising that right and engaging in our democracy. It provides a foundation upon which the students of today become the elected leaders of tomorrow. The diversity of those fifth graders absolutely influences the way they walk through the world and the challenges they encounter, as will it impact the focal points of their advocacy. So it is that civics education is among our greatest and most profound tools for achieving justice, fairness, and equity.

Massachusetts was late to the game. It was not until 2018 that the Massachusetts Civics Education Act, championed by former Senate President Harriette Chandler, was signed into law. That legislation required that civics be taught in the Commonwealth’s schools, provided civics education resources to educators, established a robust civics project program, and created the Civics Project Trust Fund to support civics curriculum implementation. We began directly funding those civics projects and curricular endeavors in 2019, my first year in the Massachusetts Senate, with $1,500,000 in the Fiscal Year 2020 budget. I am proud to have successfully led the legislative effort to increase that funding to $2,500,000 in Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025, including a line item veto override to ensure that increased funding came to fruition. Budgets are, after all, statements of values; in Massachusetts, when it comes to civics education, we put our money where our mouths are.

The policy and financial investments we have made in civics education here in Massachusetts are yielding real, tangible results. I see it in our classrooms, in the emails I receive from students across the state, and in conversations with hundreds of young people I meet in their classrooms and welcome to the State House. In addition to tours and events, selected high school students from my district participate in my annual Youth Spring Summit, a full-day State House immersive experience that culminates with policy pitches that my staff and I consider for future legislative filings. Our office is routinely augmented by contributions of student interns and fellows, spanning from high school to graduate school, and I host a virtual Youth Fall Town Hall every year to hear from my younger constituents directly. This component of our youth outreach program has generated policy innovations and investments, such as the Hey Sam youth mental health text line.

Of particular significance is the synergy between our public efforts and investments and the tremendous work of our non-governmental partners that create additional civic education and engagement opportunities, like Discovering Justice and Generation Citizen. Students of all ages literally enter the rooms where policy is made, democracy lives, and equity advances. Students transform when they are present in these spaces and connect with current policymakers; these experiences inspire young people in the moment and enable them to envision themselves in those policymaking roles in the future. The world of government becomes demystified, open to all who step in and put forth the effort to build something better and brighter. Civics education prepares young people to participate as democracy leaders both now and in the years to come.

While civics education legislation and funding has come a long way, we must not rest on our laurels. Indeed, national civics scores in 2022 declined for the first time since assessments began in 1998, and no statistically significant advancements have been achieved. To further advance democracy, we must invest even more resources in this critical educational component, and we must couple it with other legislative initiatives that uplift youth, such as allowing people ages 16 and 17 years to vote in their local elections, if the voters of the municipality adopt a younger voting age. I am proud to file this legislation in Massachusetts and continue to work toward its passage. Young people in this age bracket are already civically engaged; they campaign, fundraise, and testify before legislative committees. Likewise, many of them hold jobs and pay taxes, in addition to pursuing their educational endeavors. Expanding their access to the ballot sends a clear message that their opinions and perspectives are essential to our governance, and earlier voting helps to foster continued voting in the future as students leave home and head off to college campuses, the workforce, or service to our country.

Former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Thomas “Tip” O’Neill (D-MA) famously said, “all politics is local.” He was right. Likewise, civic engagement starts locally, and it should start early.