What Would Bayard Rustin Do? by Eric Chenoweth

Eric Chenoweth is director of the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe and principal author of Democracy Web, an online comparative study guide for teachers, students and civic activists. He worked with Bayard Rustin in various capacities in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Intoduction

We live in a reactionary age. Worldwide, the advance of freedom in the previous century did not just stall. It went into reverse. What is shocking many is that this reactionary age has taken root in the modern world’s oldest, richest and most militarily powerful democracy. Donald Trump’s return to the presidency in January 2025 has put him in a position to assert largely unchecked power to reverse America’s progress towards a multiracial democracy.

This dark period in America would not have surprised the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin. He spent decades working to end a previous period of white reactionary rule in the United States. Yet, soon after the masterwork of his career — the organizing of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom — he began warning of a political backlash against the gains made to end Jim Crow rule and to make the country a full democracy ensuring all citizens the right to vote. As he saw that backlash begin to manifest, he argued for political strategies and policies to move the country in a radical new direction towards greater equality. Whatever situation he found himself, Rustin worked to achieve a more equal, tolerant and pluralist society through nonviolent and democratic means. His life and teachings offer guidance on how perhaps to respond to today’s reactionary challenge. A new museum exhibition offers a launching point.

Speak Truth to Power

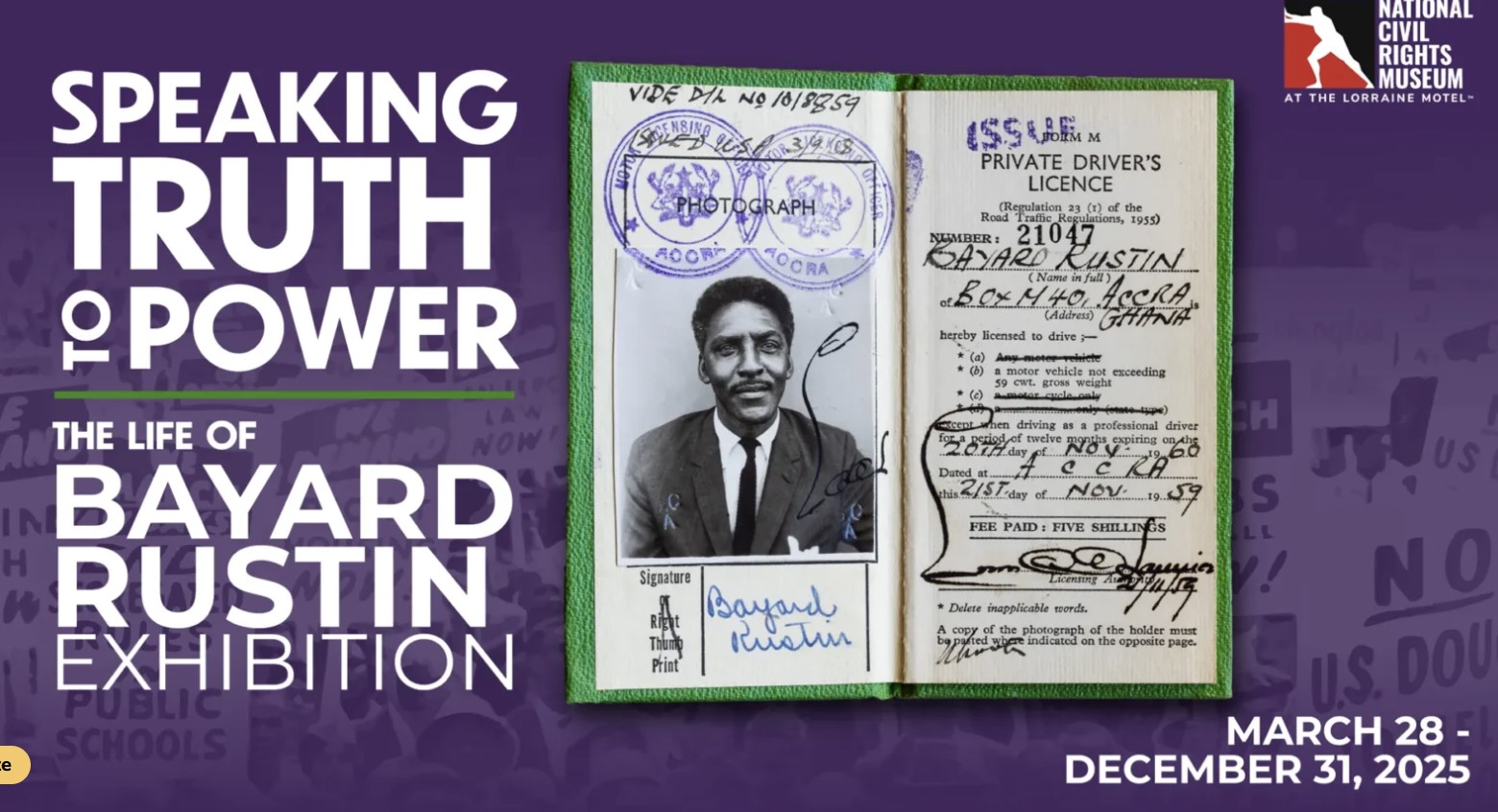

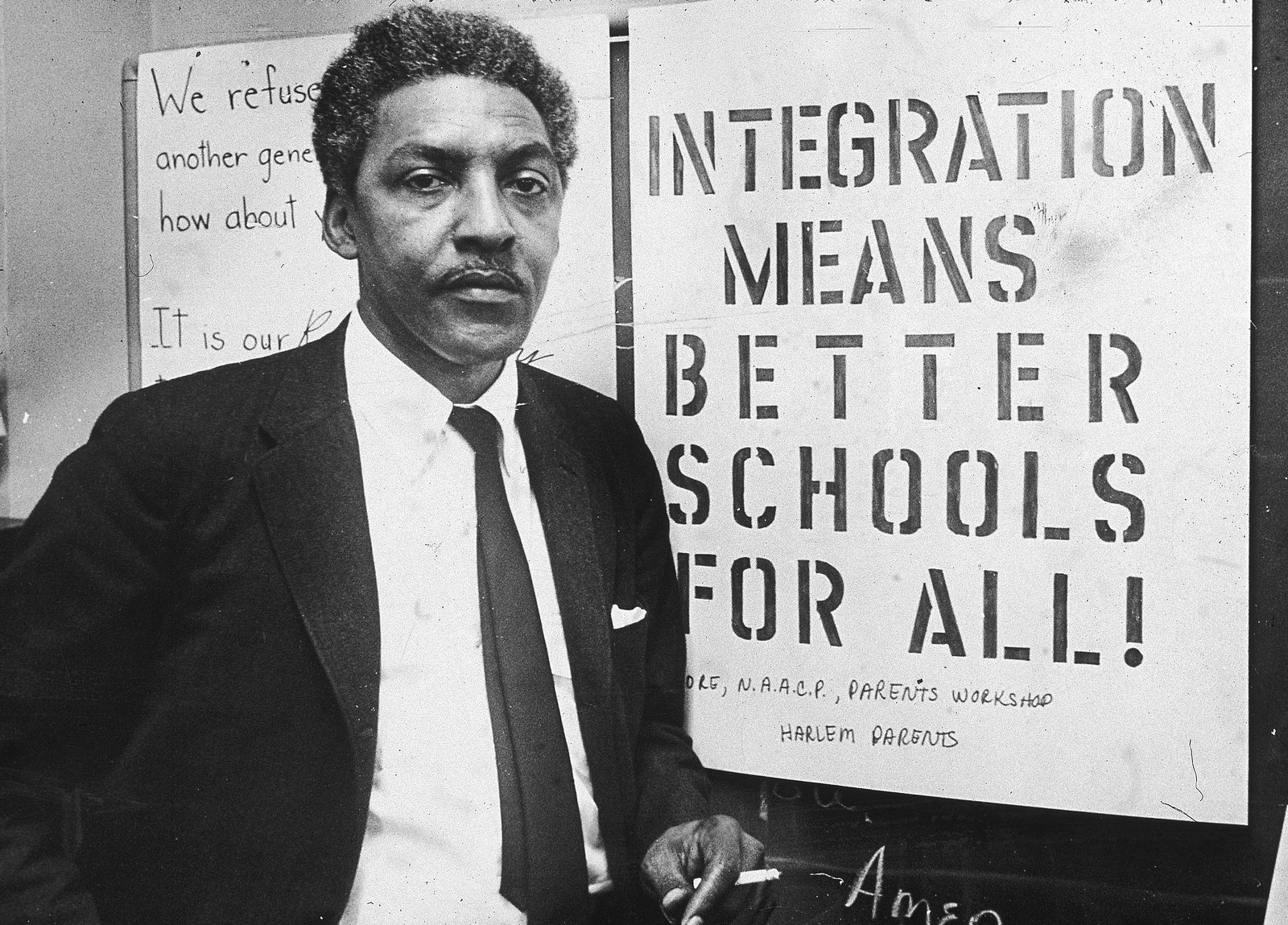

The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, located at the preserved Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, is shining a light on Rustin’s central work in the Civil Rights Movement as well as his contributions to the international peace and human rights movements. The new exhibit, “Speaking Truth to Power: The Life of Bayard Rustin,” runs through February 2026 and will serve as the basis for a permanent exhibit as part of the museum’s expansion in 2026.

Curated by art historian Gay Feldman with photographs by David Katzenstein, “Speaking Truth to Power” offers a highly interesting collection in different media that takes one back to Rustin’s time and introduces visitors to his life’s work. The exhibit consists mostly of items from collected materials provided by Walter Naegle, Rustin’s partner, who directs The Bayard Rustin Fund and has advised on a number of other projects related to Rustin’s life and work.1 One exhibit case displays original posters from speaking events and conferences in the 1940s intertwining his pacifist and civil rights beliefs. Another includes an array of photos, materials and descriptions of Rustin’s international work, including a trip to India in the late 1940s to ground his understanding of strategic nonviolence from the Gandhian movement and to Africa in the 1950s to support the nonviolent independence struggles of Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and Nnamdi Azikiwe in Nigeria. His range of talents and unique personality are shown with displays of original album covers of his early singing career and examples of Rustin’s personal jewelry and cane collections (which he always wore and carried) and of his extraordinary collection of religious and African art that he amassed over a lifetime.

A video of an interview with Naegle by the museum’s Director of History, Ryan Jones, provides a more personal account of Rustin’s life and its significance. One video section focuses on the role of Julia Rustin, the grandmother who raised Rustin and instilled in him civil rights and Quaker principles.2

As many leaders and institutions submit to Trump’s demands for allegiance to his reactionary policies, the exhibition title alone is a basic lesson for our time. It refers to a pamphlet, Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for An Alternative to Violence, that Rustin helped write in the mid-50s for the American Friends Service Committee. Rustin is often credited for bringing “speak truth to power,” a familiar phrase in Quaker circles, to popular use in civil rights, peace and other social movements. The phrase certainly reflects how Rustin, born in 1912, lived his life over 75 years: from a first solo sit-in to integrate a local movie theater in his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania; to the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first interracial freedom ride in the South to test the Supreme Court’s ban of segregation in interstate bus travel; to organizing protests across continents for a nuclear test ban treaty in the 1950s; through to his rebuke of the Democratic Party leadership for accommodating Reaganism in the 1980s. From whatever vantage point, Rustin did not let power deter him from speaking out and acting on his beliefs.

The Ten Demands

One remarkable exhibit case centers around the March on Washington that includes ephemera of many actions that Rustin helped organize leading up to it. It includes items from the original 1941 March on Washington Movement led by A. Philip Randolph to integrate defense industries and federal employment and Randolph’s 1947-48 successful campaign to desegregate the armed forces. Two pamphlets are featured from the Journey of Reconciliation (“We Challenged Jim Crow” and “22 Days on a Chain Gang,” Rustin’s account of his imprisonment in North Carolina). There is also a never-before-displayed original copy of Rustin’s earliest hand-written plans for a March on Washington. Drawn up in 1956, it shows the detail and purpose that Rustin considered necessary to the many direct actions he organized. It was the basis for three precursor marches from 1957 to 1959 — the National Prayer Pilgrimage and two Youth Marches for Integrated Schools — that he and Randolph helped organize to demand implementation of the Brown v. Board decision.

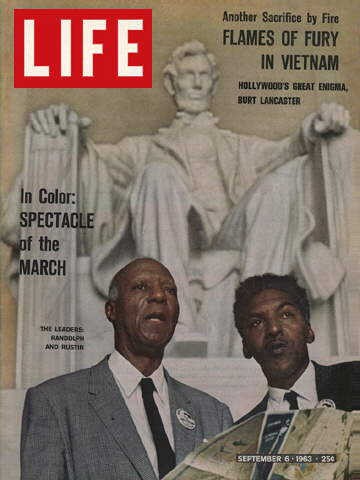

A video loop with rare footage of the 1963 march offers a glimpse of the broader strategy, discussed further below, that Randolph and Rustin brought to that time. Few remember but Rustin followed King’s powerful speech to end the march by reciting a series of demands. The massive crowd of 250,000 had come not for a vague slogan but to push for specific civil rights and economic demands on the U.S. government. Rustin printed on a flyer titled “What We Demand” and had them distributed widely prior to the march in the North and the South. On the screen, Rustin recites them in his distinct diction and asks the crowd, “What do you say?” The crowd gives its resounding ascent.

The ten demands are among the most radical set of precepts for social progress in American history. The first six relate to the March’s theme of freedom, most importantly the adoption and enforcement of civil rights legislation “to guarantee all Americans access to public accommodations, decent housing, adequate and integrated education, and the right to vote.” The last four demands, around the theme of jobs, include: a “massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages”; a national minimum wage to support “a decent standard of living”; fair labor standards in “all areas of employment”; and a “federal Fair Employment Practices Act” barring discrimination by “all federal, state, and municipal governments, employers, and trade unions” (emphasis in original).

The Source: A. Philip Randolph

As innovative as the exhibit is, it could cover only so much. Two things stand out as largely missing — both from the exhibition and the museum. The first is Rustin’s close relationship working with Dr. King, both during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and in creating the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The second is the integral place of A. Philip Randolph in the work of both Rustin and King. It is in the latter relationship that one finds the source for the Ten Demands and the basis for Rustin’s work after the march.

As innovative as the exhibit is, it could cover only so much. Two things stand out as largely missing — both from the exhibition and the museum. The first is Rustin’s close relationship working with Dr. King, both during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and in creating the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The second is the integral place of A. Philip Randolph in the work of both Rustin and King. It is in the latter relationship that one finds the source for the Ten Demands and the basis for Rustin’s work after the march.

In 1941 and 1948, Rustin had rebelled against Randolph’s national leadership. When Presidents Roosevelt and Truman each met the central demands of the March on Washington Movement and the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation, Rustin publicly criticized Randolph for not pushing further. Each time, Randolph welcomed Rustin back to his work as Rustin in turn came to appreciate Randolph’s tactical acuity and to identify more with Randolph’s foundational beliefs.

Rustin described those beliefs in a 1969 essay, “The Total Vision of A. Philip Randolph.” First, he wrote, Randolph “has understood that social and political freedom must be rooted in economic freedom.” Second, even as Randolph felt that “Negro salvation is an internal process of struggle and self-affirmation, he has recognized the political necessity of forming alliances with men of all races and the moral necessity of comprehending the Black movement as part of a general effort to expand human freedom.” And third, “as a result of his deep faith in democracy, [Randolph] has understood that social change . . . [depends] on direct political action through the mobilization of masses of individuals to gain economic and social justice.”

The March on Washington and the scope of its demands reflected especially Randolph’s vision. As recounted in Jervis Anderson’s biographies of both men, Randolph believed that a dramatic national action was needed in the 100th anniversary year of the Emancipation Proclamation to spotlight the continued lack of freedom and the resulting dire economic conditions facing Blacks in America. He was increasingly concerned about conditions in northern cities, where automation was undermining economic gains Blacks had made from moving north in The Great Migration.

In a meeting the two held in December 1962, Randolph tasked Rustin with planning a large protest in Washington, DC. Over six months, as plans evolved, Randolph and Rustin forged a coalition among the fractious Big 6 leaders of civil rights organizations and four leaders of unions and religious groups for a massive march around the themes of jobs and freedom. Not all organizations formally agreed to the full set of demands, but their leaders agreed that they should be presented to President Kennedy and Congress.

While King’s oratory took the day, Randolph, as the March’s opening speaker, set out its grand purpose:

"We want a free, democratic society dedicated to the political, economic and social advancement of man along moral lines. Now we know that real freedom will require many changes in the nation’s political and social philosophies and institutions. For one thing we must destroy the notion that Mrs. Murphy’s property rights include the right to humiliate me because of the color of my skin. The sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of the human personality.3

"It falls to the Negro to reassert this proper priority of values, because our ancestors were transformed from human personalities into private property. It falls to us to demand new forms of social planning, to create full employment, and to put automation at the service of human needs, not at the service of profits — for we are the worst victims of unemployment. Negroes are in the forefront of today’s movement for social and racial justice because we know we cannot expect the realization of our aspirations through the same old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies that have all along frustrated our aspirations."

The Freedom Budget

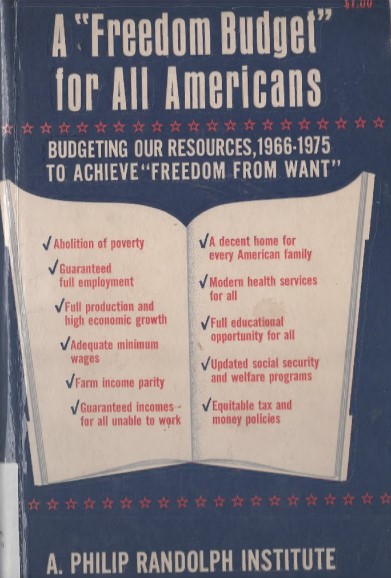

The radical language of Randolph may surprise some but, as Rustin makes clear, it was consonant with his lifelong democratic socialist beliefs as well as the raised hopes of the time. With passage of the Civil Rights Act and President Lyndon Johnson’s ambitious introduction of the War on Poverty, Randolph and Rustin believed the opportunity existed to meet their fuller goals and to create what Rustin called “equality in fact.” So did Martin Luther King, Jr., who put forward a Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged in 1964 in his book Why We Can’t Wait. In the fall of 1965, the three together proposed the Freedom Budget, a $100 billion plan (equivalent to $1 trillion today) to reorient federal spending around universal jobs training, guaranteed employment, a living wage, affordable housing, and full funding for education, health care and urban renewal. It was “What We Demand” set out in specifics.

The Freedom Budget became Rustin’s main focus. As his aged mentor stepped back, Rustin took the helm of a new organization named for Randolph and dedicated to strengthening the coalition of civil rights and labor movements. He spent the next years leading the effort for the Freedom Budget’s enactment. Rustin gained the endorsement of economists, labor leaders and civil rights organizations; he lobbied the Johnson administration; he testified before Congress; he wrote articles in prominent publications; and he spoke across the country to rally public support.

Johnson achieved much of his legislative agenda with the adoption of Medicare, Medicaid, food benefits, Head Start, later the Fair Housing Act, and other programs. Over time, these did reduce poverty, especially for the elderly; the gap narrowed in graduation rates and basic skills scores between minority and white students; among other gains. In the end, though, the hope was left unfulfilled for “a proper priority of values” and the reorganization of the economy to achieve social and economic equality. Still, Rustin never stopped advocating for the Freedom Budget.

From Protest to Politics

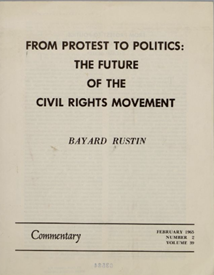

Rustin’s most famous essay is “From Protest to Politics,” which appeared in February 1965 in the then-liberal publication Commentary. It is often characterized as Rustin turning away from protest against racial injustice to advocating political compromise. In fact, Rustin did not advocate abandoning protest, nor for compromising political aims. Rather, he argued for adopting a new political strategy to achieve the Freedom Budget’s “revolutionary” economic program for “democratizing American society.”

“The central challenge for the Civil Rights Movement,” he wrote, was translating the success of nonviolent protest to gain equality in law into “a lasting majority political movement for social and economic equality.” This effort would require a change in strategy because it was “vastly more complicated” than ending legal discrimination. The reason, he explained, is that

The very decade which has witnessed the decline of legal Jim Crow has also seen the rise of de facto segregation in our most fundamental socioeconomic institutions.

He argued that neither this institutional racism nor economic exploitation generally could be overcome through programs — however justified — targeted solely to address past or ongoing discrimination. These were necessarily “zero-sum policies” in which gains for Blacks would be seen as losses by whites. As a persecuted minority, Blacks could not expect such largesse by the majority, but instead must coalesce with other political forces to adopt broad economic programs that benefitted all workers but substantially bettering the material conditions of Blacks.4

Protest against ongoing discrimination remained urgent, Rustin wrote, but with the legislative win of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to end legalized segregation, it was necessary to now address urgent economic needs. He advocated achieving these higher goals by mobilizing Black political power through massive voter registration and electoral participation efforts and enhancing Blacks’ electoral power through coalitions with those having “common interests and aims,” namely other workers.

The Enduring Backlash

In “From Protest to Politics,” Rustin wrote that the 1964 Johnson landslide against Republican Barry Goldwater represented the possibility for “a majority liberal consensus.” But, even then, he warned that the possibility also existed for a “Talmadge-Goldwater” majority taking hold in a single party, one that combined segregationist Democrats and free market Republican extremists. “[T]he Johnson landslide [did not] prove the ‘white backlash’ to be a myth,” he stated. “It proved, rather, that economic interests are more fundamental than prejudice: the backlashers decided that loss of social security was, after all, too high a price to pay for a slap at the Negro.”

The question was how fundamental in the end were those economic interests. A partial answer came with major Republican gains in the 1966 midterm elections to slow civil rights progress. A more decisive answer came in 1968 with the narrow election of Richard Nixon as president on a “law and order” platform. It signaled the full transformation of the GOP into the “states’ rights” party. The white backlash proved enduring. Libraries are stacked with books on the shifting motivations of the American electorate since then, but one thing stands out: from 1966, a majority of white voters have cast their ballots for the anti-civil rights party, often in overwhelming numbers, making a lasting multiracial governing coalition more difficult.

From the 1968 election, Rustin understood that everything that he had struggled for and hoped to achieve was at risk. In column after column and essay after essay, Rustin lambasted Nixon’s anti-civil rights, anti-Black, and anti-union economic policies. Nixon represented “the height of reactionary politics”; he tokenized Blacks with cynical initiatives like “The Philadelphia Plan”; his Black capitalism schemes were shams serving only a narrow business elite, while not uplifting the Black working class.

Rustin was particularly worried about the direction Nixon took the Supreme Court, the main institution propelling the Civil Rights Movement from the 1940s to the 1960s. With the confirmation in late 1971 of Nixon’s third appointment, William Renquist, a Goldwater acolyte, an anti-civil rights majority was solidified. Rustin wrote that the Renquist appointment was “the bleakest chapter in what has been an unremittingly sorry Nixon Administration race relations record.” The consequence was soon felt. A 1972 ruling allowed private clubs to discriminate against Blacks. Rustin wrote that the ruling meant the “end to that institution’s role as an instrument of civil rights progress and activism.” He warned of the reversals to come and argued that this made a change in civil rights strategy around economic demands even more necessary.5

The Politics of Persuasion

For Rustin, persuasion was a political corollary to nonviolent civil disobedience. He went on any number of speaking tours and addressed thousands of audiences, as indicated by the array of meeting posters shown in the exhibit. Rustin had convinced many in those audiences, Black and white, to adopt principles of nonviolence and pacifism; to put bodies on the line in civil disobedience; to commit to integrating public accommodations, schools and workplaces; and later to build alliances of civil rights and religious groups, liberals and the labor movement. It was his power in persuading interracial audiences to action (my parents were among them) that led him to believe a lasting multiracial majority was possible.

For Rustin, persuasion was a political corollary to nonviolent civil disobedience. He went on any number of speaking tours and addressed thousands of audiences, as indicated by the array of meeting posters shown in the exhibit. Rustin had convinced many in those audiences, Black and white, to adopt principles of nonviolence and pacifism; to put bodies on the line in civil disobedience; to commit to integrating public accommodations, schools and workplaces; and later to build alliances of civil rights and religious groups, liberals and the labor movement. It was his power in persuading interracial audiences to action (my parents were among them) that led him to believe a lasting multiracial majority was possible.

Rustin rarely debated political enemies but rather those he thought he could influence. Often, as when he engaged Malcolm X in debate, he spoke to audiences frustrated by the limited results of nonviolence in addressing institutional racism. In those debates, Rustin would affirm the legitimacy of the growing anger in both the North and South that Malcolm X and the Black Power movement represented, but he argued that anger was not constructive to guide strategy. He repeated often, “Let us be enraged about injustice, but let us not be destroyed by it.” Nonviolence, he would continue, still offered a more strategic means to address the oppression of Blacks than “any means necessary” or taking up arms. Rustin also contended that Malcolm X’s advocacy of Black separation from white society was a reactionary reprise of past failed strategies of Black separatism that accommodated or accepted segregation. Only demands for integration, he argued, had brought concrete progress for Blacks. (Rustin later welcomed the changing views of Malcolm X on integration before his death in the essay “Making His Mark.”)

Rustin remained sympathetic to the anger of young activists. Indeed, his arguments were generally not directed at militant Black Power advocates as much at those he believed were the major impediment to addressing institutional racism: white liberals and moderates refusing to go beyond civil rights legislation by seriously funding real solutions to social and economic problems centuries in the making.

In “The Watts Manifesto” (Commentary, March 1966), Rustin delivers a blistering critique of the McCone Commission Report, the California government’s official response to the 1965 rebellion in the Watts section of Los Angeles. He describes how he and King had gone to its destroyed areas in the wake of the 1965 unrest. Black youths they met told the civil rights leaders that their nonviolence had achieved nothing while the youths had “won” by forcing white city authorities to finally come and pay attention to their plight. To meet such desperation, Rustin argued that America’s “ghettos of despair” required nothing less than a full addressing of their needs in programs such as those included in the Freedom Budget. He continued,

"Such proposals may seem impractical and even incredible. But what is truly impractical and incredible is that America, with its enormous wealth, has allowed Watts to become what it is and that a commission empowered to study this explosive situation [comes] up with answers that boil down to voluntary actions by business and labor, new public-relations campaigns for municipal agencies, and information-gathering for housing, fair-employment, and welfare departments. . . . And what is most impractical and incredible of all is that we may very well continue to teach impoverished, segregated, and ignored Negroes that the only way they can get the ear of America is to rise up in violence."

In “Lessons of the Long, Hot Summer,” (Commentary, October 1967), he again warned liberals to heed the message of unrest in Black communities and to change the nation’s warped priorities. By now, he was less optimistic: “Many white Americans who joined the March on Washington and applauded Martin Luther King’s dream of freedom seem far less enthusiastic about helping us realize that dream when it means altering our economic structure.”6

What distressed Rustin most, however, was the reactionary policy of “benign neglect” developed in a memo by Daniel Patrick Moynihan and adopted as policy by the Nixon Administration. In a public reply, he wrote, “Moynihan has written a memo to the President on the condition of Negroes without mentioning the disastrous effect the administration’s economic policies are having upon blacks. . . . He totally neglects social and economic injustice as he narrows the problem of the ghetto down to the simple and cruelly misleading remark, ‘Black Americans injure one another.’” As Rustin reviews social conditions that Moynihan terms “pathology,” he deplores Moynihan’s blaming of Blacks for the problems of poverty imposed on them. “There is an element of social pathology here,” he writes, “but it is not in the black community as it is in a society which permits a situation like this to continue.”

Race, Class and Labor

The A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) remained the organizational vehicle for Rustin to keep advancing his mentor’s “total vision.” The APRI organized over 200 chapters of Black trade unionists around the country to enhance Black power through voter participation campaigns and union leadership training.7 Central to its mission was aligning the civil rights struggle with the AFL-CIO and its economic program. In “From Protest to Politics,” Rustin had explained why. “The labor movement,” he wrote, “despite its obvious faults, has been the largest single organized force in this country pushing for progressive social legislation.”

Rustin cited the “obvious faults” in articles because they were not easily overlooked by Blacks. Large parts of the labor movement had a history of discrimination and segregation. As the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the country’s first mass Black trade union, Randolph fought those practices for decades inside the American Federation of Labor, with some allies like the American Federation of Teachers. In the early 1960s, he finally gained greater support from the merged AFL-CIO leadership for the civil rights cause. While significant pockets of exclusion remained, there were strong efforts finally undertaken to tackle discrimination within the labor movement. In “The Blacks and the Unions” (Harper’s Magazine, May 1971), Rustin stated that the AFL-CIO was becoming one of the most integrated institutions in America, with Blacks now representing 10 percent of union membership (2.5 million members) and Black trade unionists winning more elections to leadership positions. The AFL-CIO was also the one major institution with a social and economic program similar to the Freedom Budget to answer the urgent problems of the Black community.

Rustin cited the “obvious faults” in articles because they were not easily overlooked by Blacks. Large parts of the labor movement had a history of discrimination and segregation. As the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the country’s first mass Black trade union, Randolph fought those practices for decades inside the American Federation of Labor, with some allies like the American Federation of Teachers. In the early 1960s, he finally gained greater support from the merged AFL-CIO leadership for the civil rights cause. While significant pockets of exclusion remained, there were strong efforts finally undertaken to tackle discrimination within the labor movement. In “The Blacks and the Unions” (Harper’s Magazine, May 1971), Rustin stated that the AFL-CIO was becoming one of the most integrated institutions in America, with Blacks now representing 10 percent of union membership (2.5 million members) and Black trade unionists winning more elections to leadership positions. The AFL-CIO was also the one major institution with a social and economic program similar to the Freedom Budget to answer the urgent problems of the Black community.

Rustin viewed these problems as mainly economic in nature. While he was sometimes criticized for downplaying race and emphasizing class, the two issues, as for King, were not a trade-off. Addressing class was addressing race as Rustin made clear in an address to the Tuskegee Institute (published in Dissent in November 1970):

"It goes without saying that Negroes are brutalized by racial prejudice and discrimination. What is not often remembered, however, is that were we to eliminate racism today we would have solved only part of the problem, and perhaps not even the major part. . . . Automation is eliminating thousands of jobs that were held by both whites and blacks. This problem does not spring from blackness but from a technological revolution that has affected all poor people, regardless of their race. We might psychoanalyze racism out of all the prejudiced white people in the country, but until we are willing to accept the principle that every able bodied man or woman has the right to a decent and well-paying job, we shall not have begun to attack the economic roots of racial injustice."

The Challenge of Coalition Politics

As they do with Martin Luther King, Jr., conservatives and self-described centrists today often use Rustin’s words to support their own attacks on DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion), “identity politics,” and “wokeism.” Some claim him for their support of the Supreme Court’s ending of affirmative action in higher education. Others believe he would reprise his debates with Malcolm X to today polemicize with Black intellectuals stressing America’s continuing racial divide in arguing for programs of redress and repair. They misread (or purposefully misrepresent) his actual writings.

Rustin did chastise civil rights organizations for not adopting a more unified national economic program and political strategy to address institutional racism and its economic roots in class. He specifically opposed quotas, considering them “a new form of tokenism,” and he warned that some affirmative action programs, especially in times of economic scarcity, would foster white resentment. He critiqued the “empty politics” of militant revolutionaries who took up arms or engaged in provocative direct actions.

But Rustin did not reject race as a continuing issue to be addressed, nor contest the moral argument for redress, nor even argue against embracing Black or any other identity. In his syndicated weekly columns, he backed efforts of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to tackle discrimination in the workplace; he praised the NAACP’s John Morsell for his mid-1970s initiative to bridge the divide with white ethnic groups over affirmative action; he lobbied for HBCUs as engines for Black self-affirmation and advancement. In the 1970s, he argued for extending anti-discrimination efforts to women and other minority groups. In the 1980s, he did so especially in advocating and lobbying for gay rights, which he called “the central struggle of democracy” of that time.

Rustin also championed what he called “real affirmative action” programs, meaning efforts targeting Blacks and other minorities in ways to effectively integrate them into the economy and society (the point of many DEI programs). These included the organizing campaigns of the American Federation of Teachers to unionize tens of thousands of paraprofessionals in urban areas, mostly poor Black and Latino women, who were able to gain economic dignity and educational opportunities to enter the teaching force through collective bargaining contracts. Rustin himself initiated the Recruitment and Training Program that brought many thousands of black and Hispanic youths into the exclusive construction trades unions. (It did not survive the reactionary wave of Reagan.)

Throughout, Rustin sought to rebuild the March on Washington coalition as a response to the “Talmadge-Goldwater” reaction. (“No one has proposed an effective alternative,” he wrote.) In this pursuit, what frustrated him most again were not civil rights organizations, and much less Black Power advocates, many of whom by that time had adopted the strategy of gaining local power through elections. Rather, Rustin critiqued those in the Democratic Party who distanced themselves from the AFL-CIO and derailed labor law reform. He argued that a large party faction’s support for policies harming union workers, like deregulation and free trade, was contrary to rebuilding a lasting electoral majority. In his view, a civil rights and liberal coalition absent the labor movement could not achieve a majority, as he believed the 1972 and 1980 elections showed.

Rustin’s last speech before his death, made to the Cleveland City Club in late July 1987, shows the consistency of his positions. He spoke with characteristic energy and sharpness to remind the largely business audience that Black conservatives they pointed to may have discovered all the right problems but had all the wrong solutions; that poverty caused the same so-called pathologies in poor white British slums as in Cleveland’s poor Black ghettos; that programs eradicating poverty would solve the problems of both poor white and poor Black communities; and that the broad-based universal economic program he continued to advocate for was the best means to end poverty. He lamented that few Democratic presidential candidates advocated such a vision and the one that did (he meant Jesse Jackson) “cannot win.” While the Democratic Party remained the party of civil rights and thus still the only party that could be a vehicle for Black progress, its members in Congress were nevertheless allowing “all the horrible things” Reagan was doing in budget appropriations to gut poverty programs. He concluded with a dark warning that if the Democrats did not change their approach, “I don’t know what will happen.”

A Deep Faith in Democracy

Rustin’s domestic influence waned, which led him to turn more of his focus to international work, as he had in the early 1950s supporting the pacifist and African independence movements.

Rustin’s domestic influence waned, which led him to turn more of his focus to international work, as he had in the early 1950s supporting the pacifist and African independence movements.

In that work, Randolph’s influence was again evident, with Rustin now committed more to democracy as a touchstone than pacifism. This was Rustin’s main political change over his lifetime. He continued to promote peaceful solutions to conflicts and opposed any use of arms against oppressive regimes. But Rustin wrote that he no longer saw “a political value” in pacifism “without consideration of the advance of freedom.” He redirected his actions to opposing dictatorships, advocating for human rights and humanitarian relief, and fostering democracy. He participated in dozens of missions to monitor elections and to defend the rights of refugees. Rustin also came to believe that war carried out in self-defense was just, most notably in the case of Israel. In 1973, he advocated for immediate arms deliveries when Israel’s fate was in question in the Yom Kippur War. He condemned anti-Semitism and defended Israel’s right to exist when that existence was being questioned by the very institution that established it, the United Nations, when adopting a resolution equating Zionism with racism. (In relation to today’s tragic situation, it should be noted that Rustin also supported the rights of Palestinians, called for the end to the use of violence and terror to try to achieve them, and backed all efforts at peaceful solutions to the Middle East conflict. At the core of his support for Israel was its democratic character, including its then-strong labor movement, the Histadrut.)

What was most lasting from Rustin’s Quaker upbringing was his commitment to nonviolence as a political strategy. Nonviolent resistance was then succeeding throughout the world, from the “Carnation Revolution” in Portugal in 1973 to the “People Power Movement” in the Philippines in 1986. A notable case was the rise of the Solidarity movement in Poland in 1980, where an entire society adopted the nonviolent strategy of sit-down strikes to gain the right to establish free trade unions from a repressive communist regime. Rustin went on a trip both to advise and learn from Solidarity leaders in 1980-81 and he was a loud voice against the regime’s efforts to quash the free union movement by imposing martial law in December 1981. He strongly backed the AFL-CIO’s efforts to keep the union alive with moral, financial and political assistance. In the last four years of his life, Rustin’s main focus was organizing support for the South Africa freedom movement. He believed the greater adoption of nonviolent civil disobedience there was leading to an end to apartheid. Although he did not live to see it, democratic change did indeed come to both South Africa and Poland through adoption of nonviolent strategies.

The Rustin to Come

Bayard Rustin’s belief in nonviolent civil disobedience as a strategy for achieving human freedom was given its fullest meaning in the courage, principles and actions of Martin Luther King, Jr. At the outset of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in December 1955, Rustin and Randolph both recognized the possibility of King leading a national civil rights movement, now with the moral firepower of the pulpit. They organized support and raised funds in the North while Rustin went to Montgomery to offer guidance on nonviolence practices.

In one of his last essays, “The King to Come” (The New Republic, March 9, 1987), Rustin posited that while Gandhi had pioneered nonviolence as a political means for the vast majority to overcome British colonial rule, King achieved something historically unique. He had shown the full power of strategic nonviolence by leading an oppressed minority group in a national crusade to change the unjust laws and practices of a dominant majority. He gave a model for all other minority groups facing injustice. “King’s strategy and tactics, imbued with the spirit of nonviolence, love, and affections,” he wrote, “finally made feasible the emergence, under law, of a single nation — the states truly united.”

Feasible and yet, as Rustin understood so well, still to be achieved twenty years after King’s assassination. “The second phase of King’s revolution” — the national economic program to mount the “total attack on poverty” — was never adopted. It remained for the next generation to achieve the “the King to come.” Even then, however, it seemed all too unlikely. Poverty was ever more entrenched in urban slums and leading to a new form of racism. “What makes the new form more insidious,” he wrote, “is its basis in observed sociological data. The new racist equates the pathology of the poor with race.” At the same time, he continued, “the Reagan administration is zealously seeking to roll back many of the gains King gave his life to achieve.”

Democratic Party candidates did win national elections again by crafting multiracial liberal-labor coalitions, including of Barack Obama as America’s first Black president and of Joe Biden as a stalwart pro-union president. But their reformist administrations failed to achieve the lasting political majority that Rustin had hoped for through adoption of radical economic policies. Neither president could reverse a longstanding trend starting from the Reagan era that saw increasing economic inequality and greater concentration of wealth. Nor could either president forestall the rise of a reactionary base of support behind an openly racist candidate.

As a result, the “Talmadge-Goldwater” political backlash has reached its apotheosis in the second Trump Administration. Emulating Old South regimes and relying on increased political power of former Confederate states, Donald Trump asserts authoritarian power, now through the federal government. He has unleashed a repressive national police force to deport masses of immigrants with the aim to reverse America’s demographic shift away from a dominant white majority. He has gotten rid of all DEI programs, ended civil rights enforcement, and turned the EEOC and the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department upside down to investigate supposed discrimination by minorities against the majority white population as violations of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.8 As part of an effort to maintain power, he and Republicans have launched an unprecedented assault on voting rights. With the cooperation of the Supreme Court and Congress, Trump is remaking the Constitution and the laws nearly without restraint in order to deconstruct government agencies and impose his anti-civil rights agenda on schools and universities, law firms, media conglomerates and business. As important, Goldwater’s free market extremism reigns supreme, with “Mrs. Murphy’s property rights” now corruptly exercised by Mr. Musk, Trump himself, and the growing oligarchic class of billionaires backing him.

What Would Bayard Rustin Do Today?

What would Bayard Rustin do today? One can only surmise from his life’s actions and teachings. But with reactionary politics in full hold of the country, Rustin’s legacy of radical protest and politics offers enduring lessons.

At home and abroad, he worked to expand rights and freedoms, to take up the cause of the oppressed and disadvantaged, and to promote democratic change through peaceful means. Speaking truth to power, Rustin raised his voice against injustice and threw his body into the gears of reactionary repression in acts of peaceful civil disobedience. As an apostle of nonviolence, he refused to respond in kind against acts of state violence and exhorted others to follow his example, with the understanding that the adoption of nonviolence as a political strategy was the best means to end injustice and achieve social change. Using powers of persuasion, he inspired thousands to activism and won adherents to integration, social justice, economic equality and coalition politics. He helped build Black political power through the ballot box and the union card. He acted individually and by building organizations and national coalitions to overcome the entrenched social, economic and political forces committed to maintaining legalized segregation and imposing economic inequality.

And for twenty-five years, he continuously exhorted the nation to rebuff reactionary appeals to law and order and free market extremism and to expand its understanding of equality. “It would be no exaggeration to say that the history of American political life has been the history of the struggle for equality,” he wrote in a column decrying Reagan’s transfer of wealth “from the very poor to the very rich.” In his view, “the creation of the nation’s most significant programs like Social Security, national funding for education and unemployment insurance for the jobless” was “clear proof” that the majority of Americans considered economic equality as part of that struggle. He could not abide Reagan’s “reversal of the 50-year-trend toward social justice” as a permanent expression of the national will. He argued that a lasting majority would still be built around the idea to achieve greater social and economic equality.

These principles, practices and beliefs joined Bayard Rustin together with A. Philip Randolph and are what joined them together with Martin Luther King, Jr. They are a short-term guide to mobilizing resistance to Trump’s cruel injustices and rejecting his attempt to consolidate authoritarian power. They are a longer-term guide to developing the broader organizational and political strategies for overcoming a 60-year-long reactionary backlash against the bold attempt to achieve full social and economic equality in the United States. Civil rights histories usually downplay the large synchrony of Randolph’s, Rustin’s and King’s legacies and generally overplay less meaningful disharmony. It seems time to stress the stronger synchrony, as the “Speaking Truth to Power” exhibition at the National Civil Rights Museum begins to do.

_______

1Among those many projects are Rustin, the 2023 film directed by George C. Wolfe and produced by Barack and Michelle Obama; the documentary film Brother Outsider; codirected by Nancy Kauss and Bennett Singer; the Rustin Center for Social Justice in Princeton, New Jersey, which provides resources and a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community; a young adult book called Troublemaker for Justice, co-written with Jacquelyn Houtman and Michael J. Long; and Long’s I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters (City Light Books, San Francisco: 2003).

2Naegle’s study of Julia Rustin and her own civil rights activism is part of a collection of essays edited by Michael G. Long, Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics, published by New York University Press in 2024.

3“What about Mrs. Murphy’s property rights” was the familiar refrain of segregationists and free market libertarians in debates over civil rights legislation requiring private businesses to provide equal treatment for Blacks.

4In a New Yorker article reviewing the recent voluminous literature on the subject, Idrees Kahloon, Washington Bureau Chief for The Economist, concludes that approaches like the Freedom Budget would still likely be more effective than reparations in narrowing over time the wealth gap of Blacks and whites, which has not been reduced since the 1960s (“What We Miss When We Talk About the Racial Wealth Gap,” The New Yorker, July 28, 2025).

5On the Supreme Court’s retreat on civil rights under a 50-year-long conservative majority, see “The Colorblind Campaign to Undo Civil Rights Progress,” by Nikole Hannah-Jones, New York Times Magazine, March 13, 2024.

6Martin Luther King, Jr. was even more trenchant. In Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community, also published in 1967, King wrote, “White America was ready to demand that the Negro should be spared the lash of brutality and coarse degradation, but it had never been truly committed to helping him out of poverty, exploitation or all forms of discrimination. . . . White Americans left the Negro on the ground and in devastating numbers walked off with the aggressor. It appeared that the white segregationist and the ordinary white citizen had more in common with one another than either had with the Negro.”

7Rustin delegated the running of the Institute and its programs to fellow CORE veteran Norman Hill, who had been tapped also to be the national organizer of the March on Washington. A description of the APRI’s work, along with that of earlier civil rights struggles, can be found in Hill’s recent joint memoir written with his wife Velma Murphy Hill, Climbing the Rough Side of the Mountain (Regalo Press, New York: 2023).

8See also the article by Nikole Hannah-Jones, “How the Trump Administration Upended 60 Years of Civil Rights in Two Months,” New York Times Magazine, June 27, 2025.

Documents