School District Spending And Equal Educational Opportunity

The fact that school districts vary widely in terms of funding is often lamented in our education policy debate. If you think about it, though, that’s not a bad thing by itself. In fact, in an ideal school funding system, we would expect to see differences between districts in their spending levels, even big differences, for the simple reason that the cost of educating students varies a great deal across districts (e.g., different student populations, variation in labor costs, etc.).

The key question is whether districts have the resources to meet their students’ needs. In other words, is school district spending adequate? In collaboration with Bruce Baker and Mark Weber from Rutgers University, we have just published a research brief and new public dataset that addresses this question for over 12,000 public school districts in the U.S.

There is good news and bad news. The good news is that thousands of districts enjoy funding levels above and beyond our estimates of adequate levels, in some cases two or three times higher. The bad news is that these well-funded districts co-exist with thousands of other school systems, some located within driving distance or even in the next town over, where investment is so poorly aligned with need that funding levels are a fraction of estimated costs. To give a rough sense of the magnitude of the underfunding, if we add up all the negative funding gaps in these latter districts (not counting the districts with adequate funding), the total is $104 billion.

Before moving on to discussing the brief a bit, here are four quick sentences about the new database. In keeping with our tradition of sexy names at the School Finance Indicators Database project, we call this new dataset the District Cost Database. It allows one to compare each district’s actual per-pupil spending with estimates of adequate per-pupil spending levels—that is, spending levels that would be required to achieve the goal of U.S. average test scores (a common “benchmark” with which the models assess adequacy). The data are for the 2017-18 school year. You can check out the results for individual districts with this visualization tool or download the full dataset.

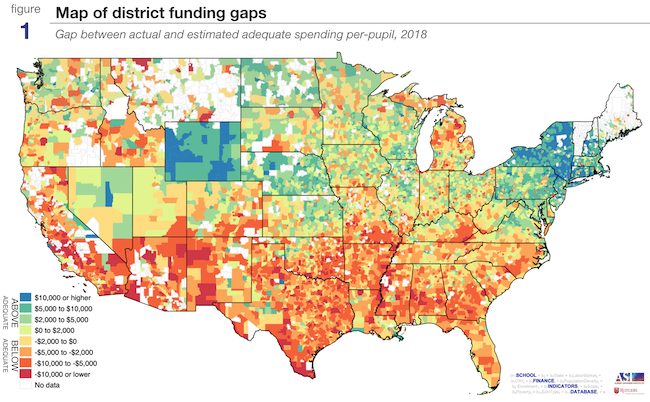

The brief presents a few aggregate results from the dataset. As you can see in the map below, many districts are funded above our cost targets (in the map, these are districts shaded in green/blue). You can find these districts all over the nation. Even in states such as Arizona and New Mexico, where large majorities of students attend schools in underfunded districts, there are numerous districts in which spending exceeds estimated requirements.

(Note: When viewing the map, bear in mind that many geographically-large districts serve very small student populations, while dozens of high-enrollment districts are barely visible on the map. Our database does exclude districts with enrollment under 100 students; these districts are shaded in white on the map.)

Yet, again, these adequately-funded districts share space (and sometimes borders) with other school systems in which funding is dramatically lower than our adequacy estimates. The map shows (in rather striking fashion) that districts with such negative funding gaps are especially prevalent throughout the southeast and southwest, but they are a national problem. They are found in rich and poor states, big and small states, and in red and blue states. This includes, for instance, Massachusetts and Connecticut: in both of these states, most districts spend above—often far above—adequacy targets, but around one in five students still attends school in a district where funding is below estimated required levels.

The average negative gap (not counting positive gaps) is $4,254 per-pupil, or 25.6 percent below the adequate level.

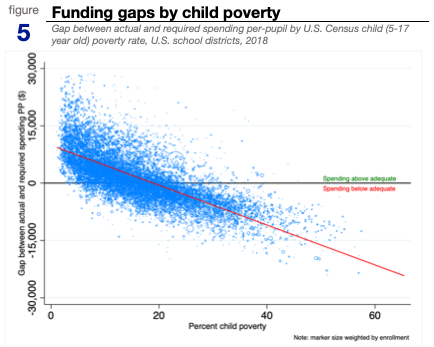

The full database also includes a selection of district-level variables, including testing outcomes (relative to the U.S. mean) and student characteristics, with which users can compare spending adequacy. For instance, we report in the brief that funding tends to be more inadequate—or less adequate—in districts with higher Census child poverty rates. You can see this in the scatterplot below, in which each blue circle is a district (larger circles represent larger districts in terms of enrollment). The red line is the average relationship between funding gaps (the vertical axis) and district poverty (the horizontal axis).

The downward slope of this line indicates (unsurprisingly) a negative relationship—that is, funding tends to be less adequate/more inadequate as poverty increases (the correlation coefficient, weighted by enrollment, is -0.70). This is a rather strong association. Virtually all of the low-poverty districts in the plot have positive gaps (funding above our estimated adequate levels), and virtually all the high-poverty districts spend below our cost targets.

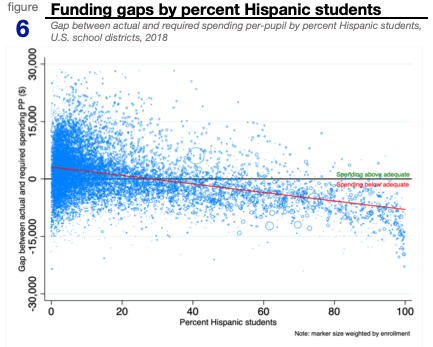

We also find a negative relationship between funding inadequacy and the shares of students of color served by districts. The scatterplot below is the same as the last one, except we have replaced district child poverty (the horizontal axis) with the share of Hispanic/Latinx students served by districts (the weighted correlation here is -0.53).

Once again, virtually none of the districts with Hispanic/Latinx shares over 80 percent also spend above our adequacy targets. In fact, 86 percent of the roughly 1,000 districts with Hispanic/Latinx student shares above 50 percent spend below estimated adequate levels. (See Baker et al. [2020] for more on this relationship.)

To be clear, our adequate spending estimates are necessarily imperfect. Estimating education costs across over 12,000 districts in 49 states and the District of Columbia is a challenge (Hawaii is not included because the state consists of a single geographically-isolated district). No model can control for everything that affects education costs, and what the models do control for is measured imprecisely (for example, we have specific concerns about reported funding data in New York and Vermont). In addition, full implementation of adequate funding levels from a perfect model using perfect data would not raise student outcomes immediately and uniformly. Real improvement is gradual and requires sustained investment.

What the District Cost Database does offer is reasonable estimates for assessing funding adequacy across the U.S. and, ultimately, for improving policy. As a whole, the results in this brief suggest that virtually no states are succeeding in their role of providing equal educational opportunity for all their students, and many are seriously failing, with student outcomes to match. (Note also that our “benchmark” outcome here—national average test scores—is not particularly ambitious.)

In the brief’s conclusion, we offer recommendations for how these data might help to guide a strategic expansion of the federal role in education finance, as well as a fundamental recalibration of how many states fund their schools. This includes: 1) targeting federal funds at districts with below-adequate funding and poor student achievement outcomes, particularly in states with more limited fiscal capacity to pay these costs themselves; and 2) incentivizing higher-capacity states to boost their own revenue and target resources according to districts’ needs.

Later this year, we will be expanding the District Cost Database to include prior years of data, as well as forecasts into the future (while still retaining the sexy name). In the meantime, once again, you can check out the full research brief, view data for individual districts with this online visualization tool, or download the full dataset (Stata or Excel format).