Are Americans Really Unwilling To Pay More To Prevent Education Cuts?

In a speech earlier today, President Obama asserted, “We will not cut education," and implied that doing so would be “reckless” and “irresponsible." The president’s heartening remark, however, comes as education funding is taking a massive hit at the state and local levels in most states, including New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Florida, and, yes, Wisconsin. The damage will likely last for many years.

In all the debate about what to cut and how deeply, there seems to be an assumption that an increase in revenue for education – to avert these massive cuts - is not an option. Although there are exceptions, very few Democratic governors are supporting tax increases to make up their states’ shortfalls, while Republicans governors are, of course, adamantly opposed.

Among many members of both parties, the presumption seems to be that raising revenue is simply a non-starter, because the American people are unwilling to pay more.

I’m not so sure. There is some evidence to suggest that this assumption deserves a second look.

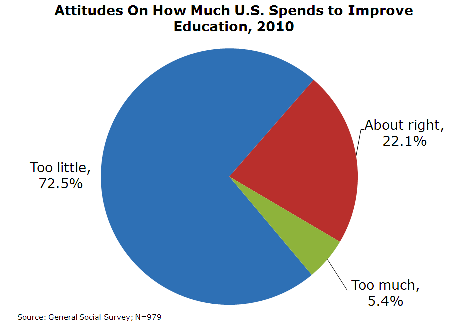

Let’s first quickly examine how Americans feel about education spending in general, by taking a look at the breakdown in attitudes using the 2010 General Social Survey, a well-respected national survey of attitudes and characteristics (I looked at this in a previous post, but that was before the 2010 data were available). The simple graph below presents the raw distribution of responses to the question of whether we spend too much, too little, or about the right amount on improving education (it is important to note that the question wording – "improve education” – probably influences responses).

There is a relative consensus here. Almost three in four Americans think that we spent too little, as opposed to roughly one in twenty who thinks spending is too high. This support seems to be lower when Americans are asked about their own schools, or when they are informed how much their districts actually spend. In any case, though, only a small minority thinks that education spending should be lower, and, due to the looming cuts, that is effectively the situation we are in right now.

But that doesn’t close the book on this, obviously. The politics of taxation are brutal, and people’s attitudes towards tax increases are complex. So there’s a few issues with these simple results that should be addressed if we’re going to even begin to question the assumption that there is political support for increasing taxes on behalf of education.

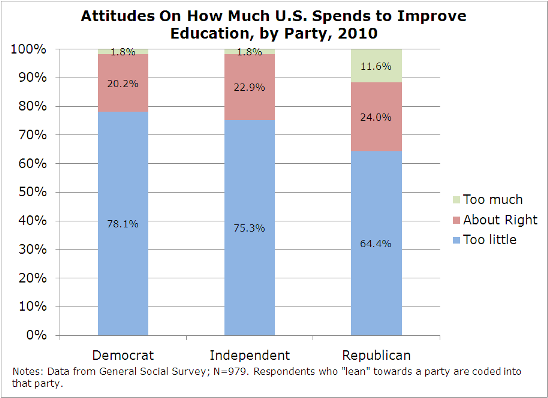

One reasonable objection is that governors (and most other politicians) are constrained – voluntarily or otherwise – to base policy decisions on the attitudes of their party’s members. After all, Republicans were elected mostly by Republicans, Democrats mostly by Democrats. If elected officials wish to keep their base of support, they must operate in observance of this political reality.

So, let’s break up the overall attitudes by political party.

The data show that there is widespread agreement that spending (to improve education) is too low. Almost two-thirds of Republicans feel that we are spending too little on education, while only 12 percent thinks expenditures are too high. Virtually no Democrats think we spend too much.

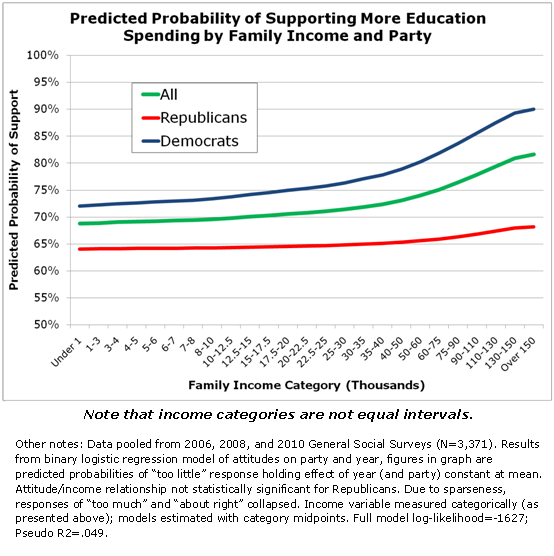

A second possible objection is that the widespread support is concentrated among lower-income Americans, who may support more spending because they won’t be the ones who have to pay. This argument is of course inaccurate – the lowest-income Americans pay almost twice as much of their income (as a percentage) towards state and local taxes as those with the highest incomes (for the poorest Americans, it’s about 11 percent; for the richest one percent, it’s about 6 percent). Whether or not a tax increase would be borne more by the poor depends on the type of tax. In any case, it’s certainly true that higher income families pay more tax dollars – after all, 5 percent of $500,000 is much more than 11 percent of $30,000. So, maybe all this support for more education spending is coming from the poor.

To consider this possibility, I estimate a quick model that predicts the likelihood of supporting more spending by income, while also controlling for political party (there are details about the model – called logit models - in the figure below, if you’re interested). To increase sample size, I pooled data from the 2006, 2008, and 2010 surveys (and I control for year in the models).

In the graph below, the green line is the predicted probability of supporting more education spending by family income category (note that categories are not equally “spaced”), while controlling for the “effect” of political party (and year). The red line is the same thing for Republicans only; the blue line is for Democrats. (Independents are left out of this graph because they are not significantly different from Democrats).

The results are a bit striking. First of all, there is no statistically significant relationship between income and spending attitudes among Republicans (interesting in itself). The line is relatively flat across the income categories, holding steady at about 65-70 percent probability of support. Among Democrats, on the other hand, there is a stronger (and statistically significant) relationship - the probability of support is considerably higher among higher-income earners, predicted at about 90 percent among those earning over $150,000 per year.

In other words, not only is predicted support at least 60-65 percent across all family income levels and both parties, it actually seems higher among those who would contribute the most (in terms of dollars, not percent of income). And, to the extent that support for educational investment does indeed vary by party and income, it seems to extend all the way from a majority to a large majority.

(Note: These results don’t change much even if I control for age, gender, education, parenthood, marital status, and race.)

The third and final possible objection is the most practical and perhaps most important – most people may think we spend too little on education, but they may not want to pay more themselves. In other words, they’re fine with increasing educational investments, but they wouldn’t want to pay for them through higher taxes. They may instead think investment should increase somewhere other than where they live (e.g., big cities), or they may want to shift spending to education from other programs.

There’s no question that Americans, even though they generally support redistribution, are a skeptical bunch about taxes. Their willingness to pay more can vary widely depending on factors such as the type of tax, question framing, and even social context. If you ask Americans about taxes generically, support tends to be low, but not always as low as you might think - a recent CBS News/New York Times poll found that, given a choice between a set of options, 40 percent of Americans expressed willingness to pay higher taxes to close state budget shortfalls.

On education, though, things are often different. For instance, a recent Pew poll (October 2010), conducted in five states (CA, FL, IL, NY, and AZ) found that roughly 65-70 of respondents were willing to pay higher taxes for education. As always, other polls find lower support, and there is plenty of underlying variation (by party, voter registration, etc.), but Americans do make some exception for education.

Consider also that cuts in state funding for education are often de facto tax increases among higher-income Americans. Those who can afford small classes, nice buildings, and highly-paid teachers are usually willing to pay for them – and they typically make up for any decrease in state funding by agreeing to increases at the local level (e.g., property taxes). As a result, education cuts often don’t affect more affluent families nearly as much (they make up the difference locally). In other words, support for averting cuts through taxation is evident in the frequency with which it occurs, at least in more affluent communities. Lower-income Americans would likely do the same, but they don’t have the resources.

Overall, then, Republicans who claim to have a “mandate” to decrease education spending (a mandate, by the way, based on an election in which three out of five eligible voters didn’t show up) have benefited greatly from the assumption that their constituents would oppose a tax increase for any reason. Democrats may wish to avoid these cuts, but they also appear to be operating under the “tax hikes are a non-starter” assumption.

I am unconvinced that they’re correct. To the contrary – the vast majority of Americans think we spend too little, and while my analysis is exceedingly simple (and polling results notoriously unreliable), many people may be willing to pay more out of their own pockets (to say nothing of other options, such as enforcing corporate tax laws or making state/local tax systems more equitable). This is especially salient given our current situation, in which taxes would be averting large decreases in education spending, rather than increasing “normal” levels.

It’s probably too late to avoid most of the draconian education cuts that will take effect this year. But the issue is hardly moot, since our budget troubles are likely to continue for at least two or three more years (in most states). Most states will not be able to avoid some decreases no matter what they do. But the cuts will be truly devastating, and mitigating them should at least be considered as an option.