Interpreting Achievement Gaps In New Jersey And Beyond

** Also posted here on "Valerie Strauss' Answer Sheet" in the Washington Post

A recent statement by the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE) attempts to provide an empirical justification for that state’s focus on the achievement gap – the difference in testing performance between subgroups, usually defined in terms of race or income.

Achievement gaps, which receive a great deal of public attention, are very useful in that they demonstrate the differences between student subgroups at any given point in time. This is significant, policy-relevant information, as it tells us something about the inequality of educational outcomes between the groups, which does not come through when looking at overall average scores.

Although paying attention to achievement gaps is an important priority, the NJDOE statement on the issue actually speaks directly to the fact, which is well-established and quite obvious, that one must exercise caution when interpreting these gaps, particularly over time, as measures of student performance.

The central purpose of the statement is to argue that, while New Jersey's overall test scores are among the best in the nation, achievement gaps – and their closure – should be the big focus of the state’s education policy, and the primary gauge of its success or failure. In an attempt to justify this view, and address directly the question of why the gap matters, the NJDOE statement asserts:

[The achievement gap] matters to the nearly 40% of our students can't read at grade level in 3rd grade - an indicator closely tied to future success in school. It matters to the thousands of students that drop out of high school or even before high school each year. And it matters to a high school dropout that faces a radically different future than a college graduate.This is more or less a non-sequitur. The cited statistics –40 percent of third graders aren’t reading at grade level and a high dropout rate – are troubling and important, but they’re not achievement gaps. In fact, the achievement gap as typically defined might actually conceal these outcomes.

The existence of a gap only tells you that there are differences in outcomes (e.g., scores) between two groups, which are almost always defined in terms of income or race. States and districts could have a large achievement gap, but still contain a relatively high proportion of students reading at grade level. For instance, a relatively affluent district could see virtually all third graders reading at grade level, but still have a significant achievement gap – with one group (e.g., high-income students) performing much higher than the other. Conversely, one could imagine a struggling district with a much smaller gap, but where virtually all students still scored below grade level.

If the NJDOE wants to make the (perfectly compelling) case that something should be done to help the 40 percent of third graders who it says cannot read at grade level, then those are the statistics they should cite. But it's a little perplexing to use these figures, by themselves, as a justification for their focus on race- and income-based achievement gaps, which are a different type of measure. The better argument would have been to simply say that the state’s overall scores are quite high, but that this masks the fact that many students are still struggling. Differences in scores between subgroups are usually an underlying component of overall performance, but the latter might be obscured by the former, and vice-versa. It's critical to examine both.*

But the big issues arise when achievement gaps are viewed over time. This is the primary focus of the NJDOE statement (as well as NJ's overall 2011 education reform agenda). The state presents a bunch of graphs illustrating the trend in gaps between 2005 and 2011. The accompanying text asserts that race- and income-based gaps as measured by the state’s tests have been persistent since 2005 (NAEP results support this characterization – for instance, the difference between students eligible and not eligible for free/reduced-price lunch in 2011 is not statistically different from that in 2005 in any of the four main assessments).**

Differences in performance between student subgroups are important, but the “narrowing of the achievement gap," as a policy goal, also entails serious, well-known measurement problems, which can lead to misinterpretations. For example, as most people realize, the gap between two groups can narrow even if both decline in performance, so long as the higher-performing group decreases more rapidly. Similarly, an achievement gap can remain constant – and suggest policy failure – if the two groups attain strong, but similar, rates of improvement.

Put differently, trends in achievement gaps, by themselves, frequently hide as much as they reveal as far as the performance of the student subgroups they are comparing. These issues can only be addressed by , at the very least, decomposing the gaps and looking at each group separately. And that’s precisely the case in NJ.

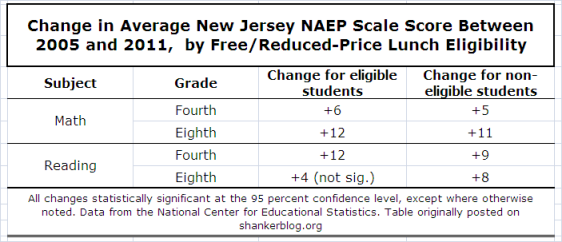

The simple table below compares the change (between 2005 and 2011) in average NAEP scale scores for NJ students who are eligible for free/reduced-price lunch (lower-income) versus those who are not eligible (higher-income). I want to quickly note that these data are cross-sectional, and might therefore conceal differences in the cohorts of students taking the test, even when broken down by subgroups.***

Only in eighth grade reading was there a discrepancy between subgroups –the score for the 2011 cohort of FRLP-eligible students is statistically indistinguishable from that of the 2005 cohort. This means that, by social science conventions, we cannot dismiss the possibility that the former change was really just random noise. So, to the degree that there was a widening of the NJ achievement gap in eighth grade reading between 2005 and 2011 (and, as stated above, it also wasn’t large enough to be statistically significant), it’s because there was a discernible change for one subgroup but not the other. This exception is something worth looking into, and it is only revealed when both groups are viewed in terms of their absolute, not relative scores.

Similarly, if one looks exclusively at achievement gap trends in a simplistic manner, the substantial increases between cohorts in seven out of eight subgroup/exam combinations would be ignored, as would the fact (not shown in the table) that both eligible and non-eligible students score significantly higher than their counterparts nationally on all four assessments.

Roughly identical results are obtained for the subgroup changes if the achievement gap is defined in terms of race – there were equally large increases among both white and African-American cohorts between 2005 and 2011 in all four tests except eighth grade reading, where the change between African-American student cohorts was positive but not statistically significant.

(One important note about the interpretation of these data: The cohort changes among seven of the eight groups shown in the table [or the gaps in any given year], assuming that some of it is "real progress," should not necessarily be entirely chalked up to the success of NJ schools per se. This represents the rather common error of conflating student and school performance. That is, assuming that students’ testing results [and changes therein] are entirely due to schools’ performance – though it’s well-established empirically that this is not the case. Some of the change is school-related, while some of it is a function of non-school factors [and/or sampling variation]. Without multivariate analysis using longitudinal data, it’s very difficult to tease out the proportion attributable to instructional quality.)

Nevertheless, the simple data above do suggest that an overintepretation of the achievement gap as an educational measure, without, at the very least, attention to the performance of constituent subgroups, can be problematic. Yes, in any given year, the differences between groups can serve as a useful gauge of inequality in outcomes, and, without question, we should endeavor to narrow these gaps going forward, while hopefully also boosting the achievement of all groups.

But it’s important to remember that the gaps by themselves, especially viewed over time, often mask as much important information as they reveal about the performance of each group, within and between states and districts, as well as the ways in which the actual quality of schools interact with them. Their significance can only be judged in context. States and districts must interpret gaps in a nuanced, multidimensional manner, lest they risk making policy decisions that could actually impede progress among the very students they most wish to support.

- Matt Di Carlo

*****

* It’s also worth noting that the achievement gap as defined above – the difference in scores between students eligible and not eligible for free/reduced-price lunch - is not statistically different from the U.S. public school student average in three out of four NAEP tests (with the exception being eighth grade reading, where the NJ gap is moderately larger).

** Most of the data presented in the NJDOE statement are achievement gaps on the state’s tests, as defined in terms of proficiency rates – that is, the difference in the overall proficiency rate between subgroups, such as students who are and are not eligible for free/reduced-price lunch. Using proficiency rates in serious policy analysis is almost always poor practice – they only tell you how many students are above or below a particular (and sometimes arbitrary) level of testing performance. However, measuring achievement gaps using these rates, especially over time, is almost certain to be misleading– an odd decision that one would not expect of a large state education agency. In this post, I use actual scale scores.

*** Since most achievement gaps compare two groups of students, they often mask huge underlying variation. For example, the comparison of students who are eligible versus those not eligible for free- and reduced-price lunches completely ignores the fact that this poverty measure only looks at students below a certain threshold, thus concealing the fact that some students below that line are much more impoverished than others, making comparisons between states and districts (and over time) extremely difficult (making things worse, income is a very limited measure of student background). On a related note, one infrequently-used but potentially informative conceptualization of the achievement gap is the difference between and high- and low-performing students (e.g., comparisons of scores between percentiles).

In order to be valid, any scientific study must be designed to control all the variables except the one being tested. The use of standardized achievement tests controls almost no variables. Even within a single district, economics, ethnic diversity, family structure and other factors may significantly change in only a few years. Changes in standardized tests may be valuable in determining the success of the philosophy of a single district as it attempts directional changes to meet demographic changes, but to use a single factor out of many others that are not even identified, much less controlled, challenges the credibility of the conclusions of teacher effectiveness based on student achievement tests.